‘The Breezeblock’ mix turned 25!

On October 12, 1998, on London’s BBC Radio 1, Liam Howlett presented his legendary mix for the Breezeblock show. Four months later, it would become widely known as The Dirtchamber Sessions. Exactly 25 years have passed since its broadcast, and in honor of this, we have prepared an extensive article dedicated to the history of the original mix: its concept, the technical details, as well as all existing versions of this mixtape and some other rare stuff.

Liam Howlett for SonicNet: I was just trying to give people an insight into what goes on in my head when I’m writing music for my band, an insight into my inspirations. It wasn’t difficult to fill an album up with some of my favorite tracks. It was just a matter of getting them to fit together right and getting them in a certain style that was more related to the B-Boy culture than a seamless dance mix.

The popular electronic music show Breezeblock, hosted by journalist and DJ Mary Anne Hobbs, was a staple in the electronic music community for 13 years, running from February 1997 to September 2010. Throughout its existence, Breezeblock featured numerous intriguing mixes and guests, including Jason Pierce, DJ Shadow, Dubstep Warz, and many others. However, a pivotal moment in its history was undeniably the mixtape presented by The Prodigy‘s mastermind.

The fateful broadcast took place on October 12, 1998 (and not on the 13th, as many mistakenly believe!). Right after it, Liam Howlett’s mix started circulating on bootleg cassettes, passed from hand to hand by fans, and it gained significant popularity.

Liam Howlett on BBC Radio 1 (12 October 1998): Before the band started, I was really into mixing and stuff, especially on a more hip-hop level. I used to do it every week, making tapes and sharing them with my mates. So, when you asked me to do this, I thought, why not?

By the way, Liam is well-acquainted with the DJ culture. As early as 1987, at the age of 15-16, he secured both the first and third places in a DJ contest hosted by the legendary Mike Allen on Capital Radio. We’ve detailed this period in our article about Cut2Kill, Liam’s first hip-hop group. Shortly before this, Liam was making his first “mixes” using a regular cassette recorder and the “pause” button – perhaps some of you guys did the same!

Mary Anne Hobbs: You used to make mix tapes as a kid, right? Could you tell us a bit about that?

Liam Howlett: I didn’t really get into turntables at first. My first attempts at mixing were kind of like old-school mixing, using the analog pause button on the stereo. Some of the later digital ones had a slight two-second delay, which didn’t work as well. I did quite a lot of little pause button mixes, and that was my first foray into mixing.

One day, Liam heard Grandmaster Flash On The Wheels of Steel, and it totally blew his mind. He thought that if he bought turntables, he could make similar stuff. In an interview from the Dirtchamber promo, Liam shared an amusing story from that time.

Liam Howlett for Mary Anne Hobbs (February 1999): Later on, during my summer holidays in school, I saved up and bought two Technics turntables and a mixer. For the next two or three years, none of my friends saw me because I became a total hermit, just focused on learning how to mix. I was constantly buying hip-hop records, spending every Saturday at Groove Records in Soho. It’s funny, actually, because Tim Palmer, who used to run XL, also owned Groove Records. I remember his mom worked there, and we’d go in as young B-boys. We’d see this older woman working there, and it was a bit of a laugh. We’d go up to her and ask for the latest underground hip-hop tunes, like Ultimate III: ’Ultimate III Live!’. She always knew what we were talking about. It was pretty amusing to us, that this 70-year-old woman had more knowledge about the music than we did.

The work on the mix for Breezeblock took place in the autumn of 1998 in Liam Howlett’s home studio in Essex, and it took less than a week in total. However, few people know that the story of the mix began six months before that — Mary asked Liam to create a special mix for her show in early 1998. In general, the idea for the Breezeblock set might not have occurred to anyone if it weren’t for the official biographer of The Prodigy and a long-time friend of Howlett, the well-known Martin James.

In his book titled ‘We Eat Rhythm’, Martin James mentioned the interview with both James Lavelle and DJ Shadow in early 1998, that he was lucky enough to be present. During a break for photos, he engaged in a conversation with Mary Anne Hobbs and her producer Jane Gordon about their highly acclaimed ‘Breezeblock’ shows. In the discussion, he proposed the idea of inviting Liam to participate. Surprisingly, Mary Anne and Jane were unaware of Howlett’s background as a DJ, and they both expressed enthusiasm about the idea. Martin recounted that the next day, he reached out to Liam to share details of the conversation, and Howlett expressed genuine interest in the idea.

Obviously, at the beginning of 1998, Howlett could easily have turned down this offer. Less than a year had passed since the release of The Fat Of The Land, and The Prodigy were not only one of the most sought-after groups in the world but also the most popular among bands playing electronic music. The guys were almost constantly on tour in support of the album, and Liam simply didn’t have the energy or time for any extra activities besides concerts. Moreover, according to his own words, he was never a fan of DJ mixes.

Liam Howlett for Mary Anne Hobbs (February 1999): We were touring for The Fat of the Land back then, and I was really craving a break. […] When you first asked me, I turned it down a couple of times. Someone at the record company sent it to me, and at that point, I was really enjoying having some time off. But then I thought it would be great to revisit something I used to do and take my mind off writing music. I was just in a phase of wanting a pause. I had done as much as I could in my other studio (Earthbound), and I was in the process of moving house.

However, the idea of a DJ mix did stick in his head, and a couple of months after that fateful phone call, Liam finally shared his plans with Martin about doing something for Breezeblock. The revival of old-school and the new wave of b-boy (breakdancing) movement, which had swept across Europe at that time, played a significant role in this decision.

We extensively covered this period in our article about 1998, and here’s a small excerpt to provide context. Among the most memorable moments of that period, one can recall the first official release from the annual international breakdance battle, as well as the 1999 “Freestyler” by Bomfunk MC’s, and the controversial hit from Run DMC, It’s Like That, remixed by Jason Nevins. It was controversial because it merely exploited old-school elements, essentially being a straightforward club house banger. Liam immediately disliked this tune and took every opportunity to express his strong negative opinion about it.

Liam Howlett for Select: I suppose the main reason I did the mix was as an answer to all of the old-skool revial shit that’s been going down. To me it was just shit, all these house DJs suddenly saying they were into hip hop. Most of those DJs aren’t fit to tie phat laces let alone wear’ em, you know what I mean?

By the time The Prodigy finished their tour in August 1998, Nevins’ ‘It’s Like That’ was playing literally everywhere, and Liam, having caught his breath after the tour, immediately got to mixing. Firstly, it was a way to shift his focus to something fresh and take a break from music production. Secondly, it was a chance to definitively show who the real king of old-school was.

Liam Howlett for Mary Anne Hobbs (February 1999): To be honest, it just came at the right time for me. […] I felt it would be cool to go back into the studio and do something different from writing music. It was really refreshing to pull out 100, or 200 records and listen to them all at once. That was really inspirational for me as an artist, just sitting down and absorbing all those different productions and beats. I think it really helped me in writing my own music, or it will do when I start doing it eventually, yeah.

According to Liam, he had never been one to go out and buy dance music, so his records mainly consisted of old-school hip-hop and breaks. He was fully aware of his entire collection, so it was just a matter of going through it and selecting the records he felt had influenced him over the last eight years, from 1990 to 1998. This resulted in a diverse selection of songs. Howlett is frustrated by the fact that not many people realize that those records are great songs in their own right, like, people tend to skip to the whole tune to find the drum breaks and overlook the rest of it. As a result, he selected the records that were somehow connected to each other without trying to destroy the sort of myth of the songs. By the way, it only took 5 days to create the original mix for Breezeblock!

Liam Howlett for Mary Anne Hobbs (February 1999): I haven’t got decks set up at home, two turntables set up to just go into the studio mix. I’ve got one set up I sample off, and I had another deck in the shed, so I had to pull that in and just basically set it up. It’s strange because I’m not a DJ, I don’t claim to be. The original idea was to have all the equipment there and do it raw, totally spontaneous. And that’s what I did. It wasn’t planned, it just happened. With each song, I didn’t work out what I was going to do. It evolved as it went along. The original mix I did for your show included tracks like The Beatles. In the beginning, I had the idea to mix these old tracks and breaks to give them a ’90s sound, but it didn’t work out for some of the tracks on the release.

Because at that moment Liam was making the mix essentially for his own pleasure, without planning any official release, he didn’t feel any pressure or tension. Back then, he thought the mixtape would be played on the radio just a couple of times, so he simply enjoyed the process.

Mary Anne Hobbs: I’ve got to ask you, what was on your rider at this time?

Liam Howlett: Oh, cigarettes and beer. I just got in there, smoked loads of cigarettes, drank loads of beer, and kind of just did that for about five days, this is more or less what I lived on. My studio is in my house, so I could just get up in my dressing gown, go down there, and put the mics together to start working. It was a really relaxed, no-pressure type of thing. It was really cool, you know?

Liam Howlett for Mixmag: Recording it was one of the most inspirational times I’ve had in ages. Just sitting listening to all your favourite records over a few weeks is such a brilliant thing. I’m not a regular DJ, so I never sit down and listen to records that much.

Many often wonder questions like “how was this mixtape actually recorded?”, “was it ever played live on the radio?” and “was it ever played from start to finish?”

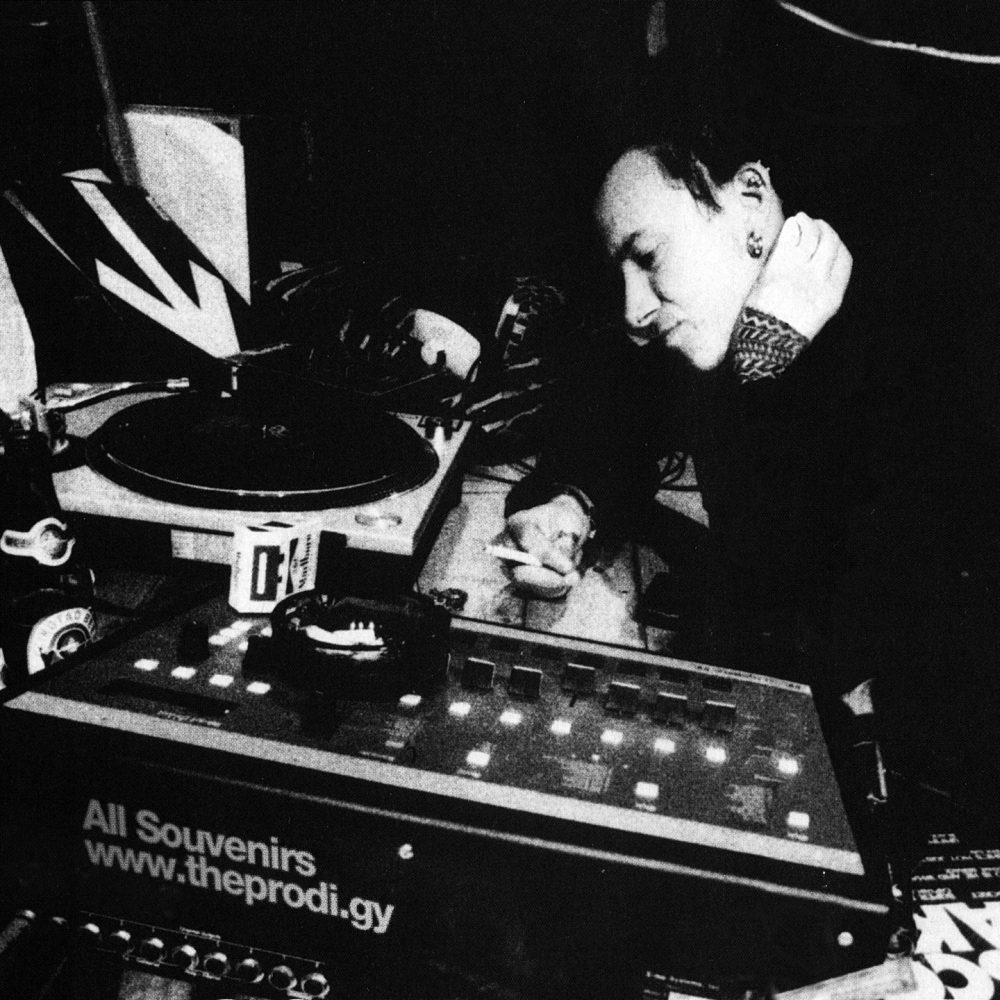

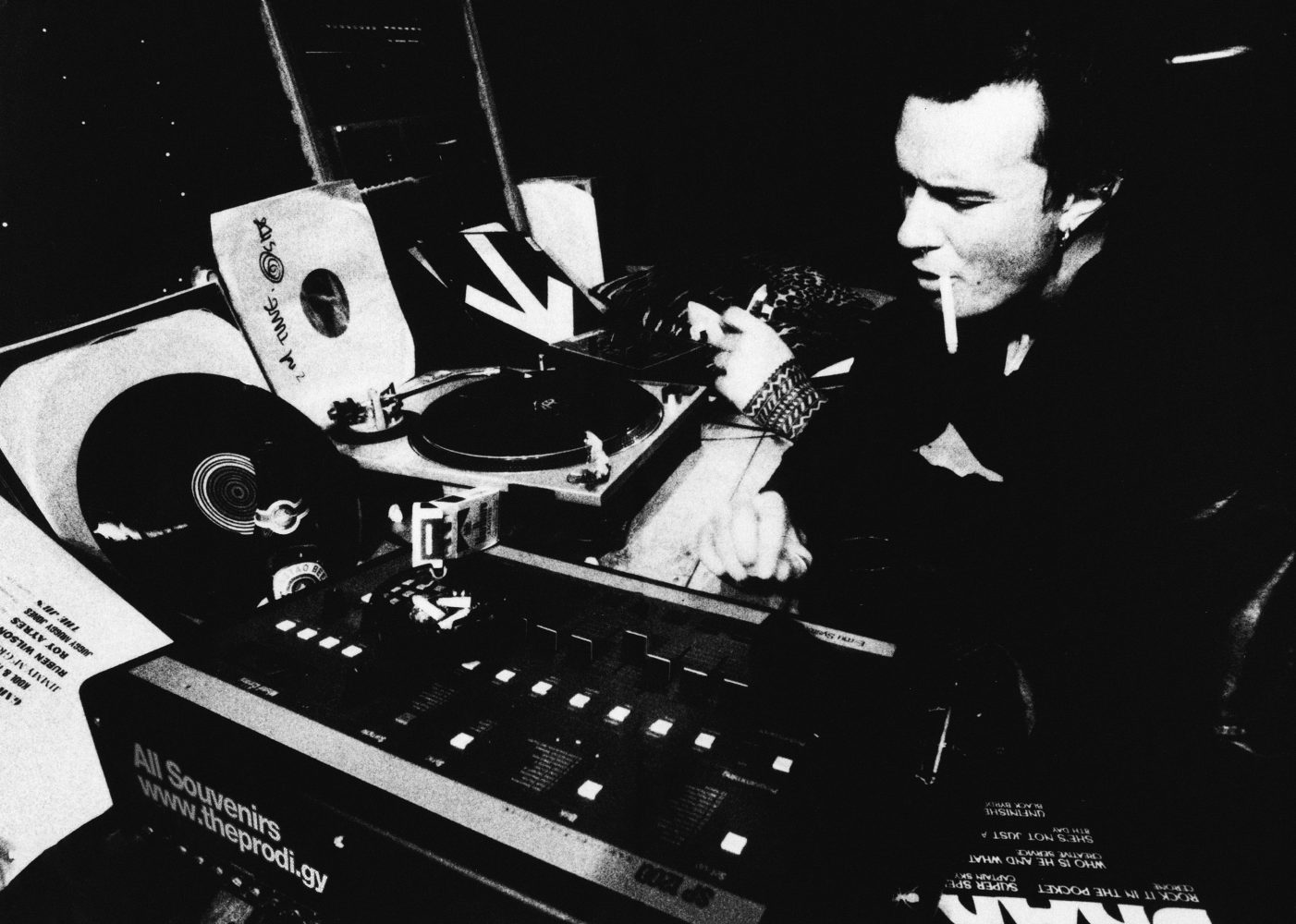

To begin with, the mix isn’t what’s commonly referred to as a “one-taken” mix, meaning a continuous live DJ set. Despite Liam mentioning in interviews his classic pair of vinyl turntables (in the 90s and 2000s, he used Technics SL1200), complex cut-up mixes like this are typically done in “blocks” of 2-3 mixed tracks. Each successive block simply starts with a track that follows the one in the previous block. Later, all these numerous blocks are combined together using a regular audio editor – you don’t even need to use any specific DAW for this.

As for mini-samples and loops, an E-MU SP-1200 sampler was used to handle them. During the mixing of a particular block, pre-recorded beats and pieces were triggered from the sampler.

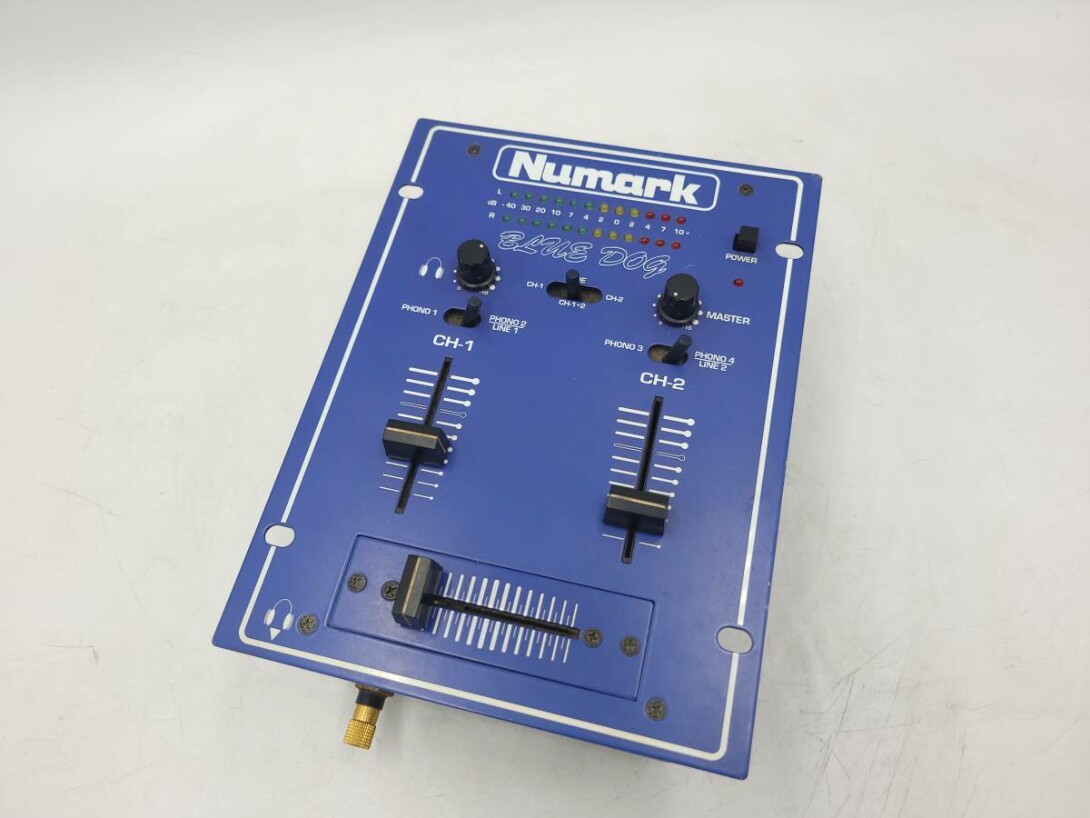

Among the equipment used for Breezeblock, the simplest DJ mixer, the Numark Blue Dog DM900, was also noticed. This mixer doesn’t even have EQ, indicating that the main emphasis in mixing technique was placed not on smooth transitions between tracks, but on how well the tracks themselves were compiled in relation to each other, which is crucial for cut-up mixes.

During the work, Liam also used an old-school synth, Roland VP330 Vocoder Plus, which transforms a regular voice into a “robotic” one. It’s evident that it was used for the 2nd edit of the mix with Intro Beats, which also made it into the final Dirtchamber. The overall mix was recorded on a digital ADAT tape recorder – most likely, it was an eight-track Alesis ADAT.

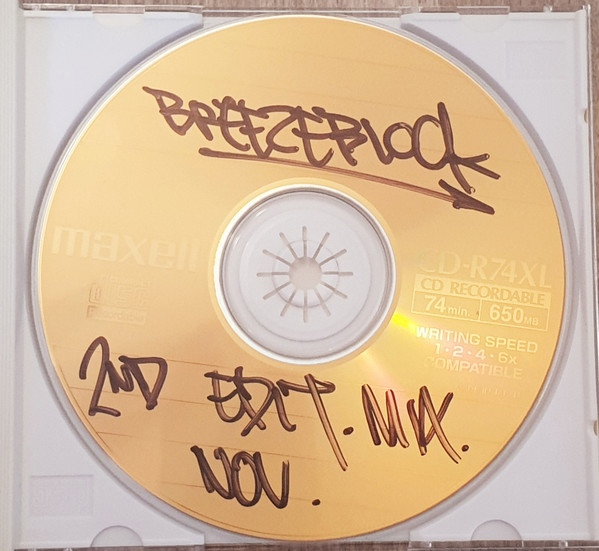

After the final edit, the mix was simply burnt onto a CDr and sent to the BBC, where it was broadcasted live. While you can find studio recordings of the second edition and the final Dirtchamber on the internet, the CDr with the original Breezeblock mix hasn’t surfaced anywhere in 25 years. The only exception is a cassette off-air recording from the studio master, which was sold a few years ago on Ebay.

It seems that even the BBC couldn’t find that original CDr in their archives, as for the re-airing of the mix in honor of the band’s 30th anniversary, they seem to have played an old tape rip that has been circulating online for many years.

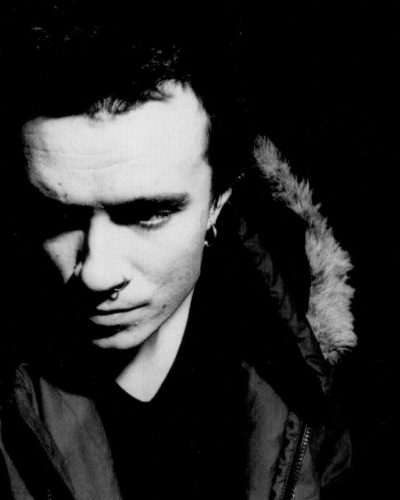

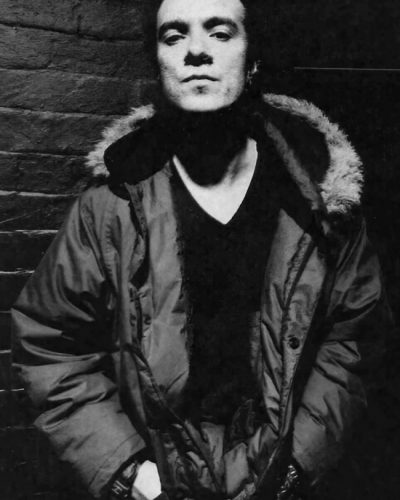

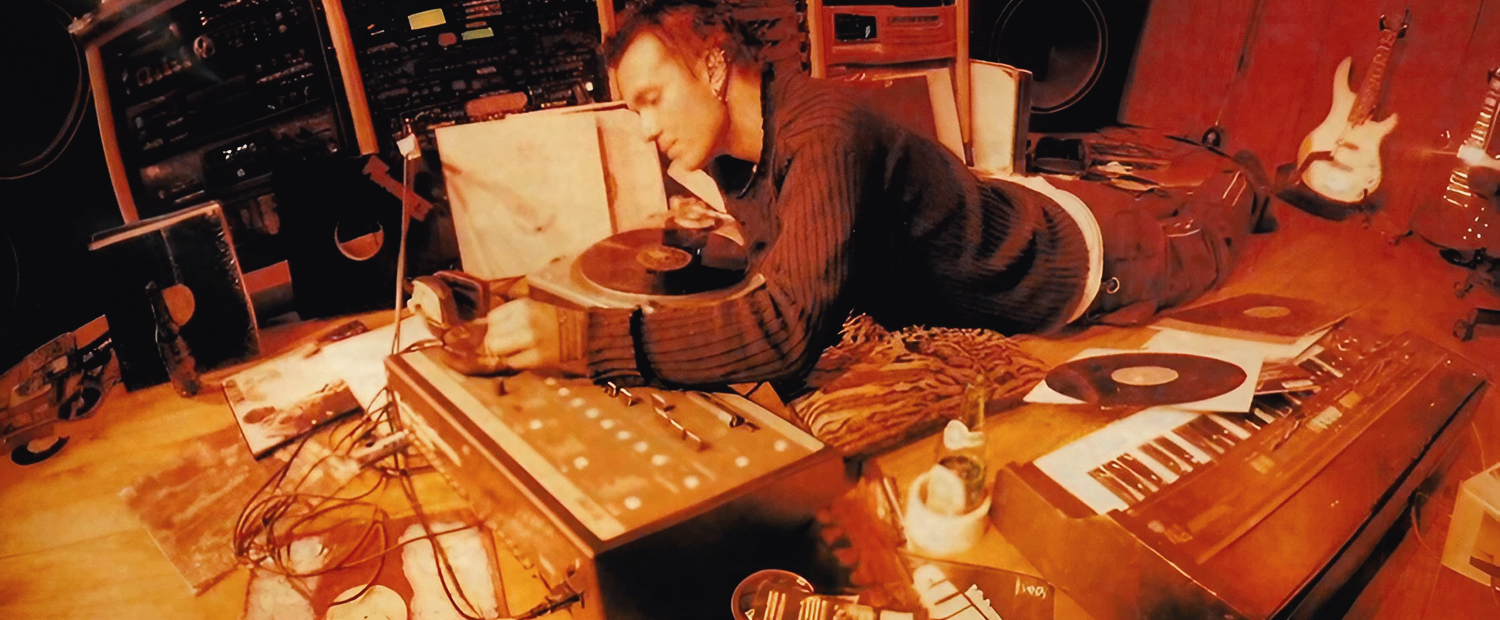

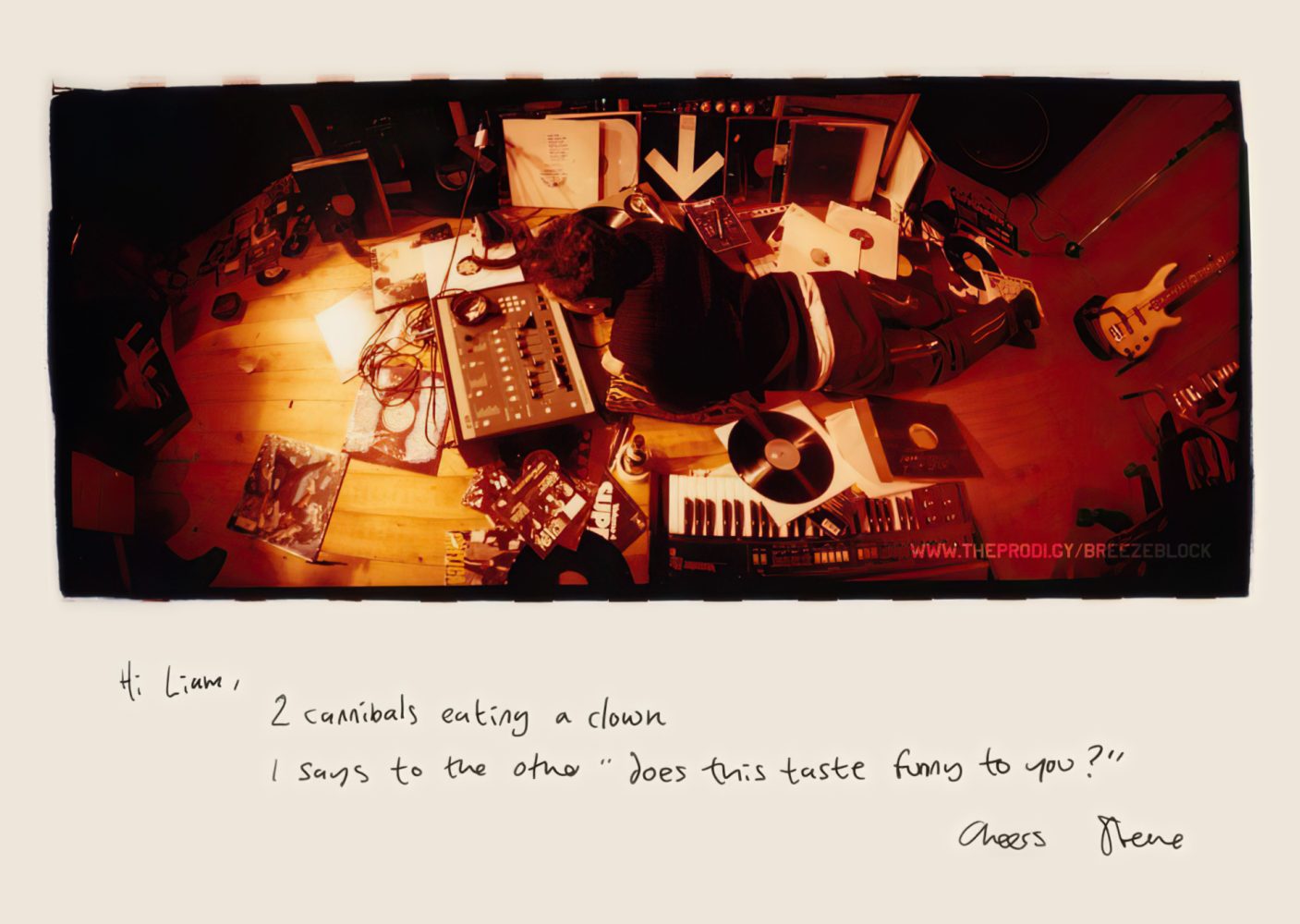

All the mentioned equipment can be seen in Steve Gullick‘s photographs taken during the mixing process in Liam’s Essex home studio, where he is lying on the floor surrounded by records, beer bottles, and ashtrays. According to Liam, during one of the days when about half of the work was done, he called Richard Russell from XL Recordings to share his impressions of the mix. Richard suggested inviting a long-time friend of the band, photographer Steve Gullick, known for his shots of Kurt Cobain, Nick Cave, Lou Reed, and dozens of other legends, to the studio. This resulted in a series of stylish shots, some of which were later used in the design of The Dirtchamber Sessions and for the release’s promotion in the press. As we’ve noticed, this single photoshoot captures the moment of recording not the original version of the Breezeblock mix that aired on the radio, but its second edition, when Liam was adding some blocks, including the intro with the robot voice. This is why you can see the Vocoder Plus in the photo and the absence of the second turntable. Therefore, most likely, these photos were taken after the broadcast, either in the second half of October or already in November 1998.

By the way, a couple of years ago, we made a high-quality remaster of the aforementioned cassette rip: to this day, our remaster is the best-sounding version of the Breezeblock mix among all those circulating online! Here’s the job that was done:

- We combined the two best-quality radio rip recordings (one is 01:03:27 in 128 kbps, and the second is a flac recording of 55:17 with some missing parts of the mix and sound issues).

- We removed the sub-frequencies below 10 Hz and hum.

- We aligned the phase of the signal.

- For part of the 128 kbps rip, the high-frequency spectrum was carefully matched to the second rip to make any differences less noticeable.

- We removed tape noise where possible and inserted missing parts of the mix.

- The parts of the mix that were lower in volume were gently normalized in relation to the entire recording.

- The ending of “It’s Just Begun” was copied from the Dirtchamber (to remove Mary’s voice) and matched with the existing tape sound to make the transition seamless.

- Other less noticeable sound defects were meticulously fixed.

You can find a download link to our remaster in hidden section on our site!

FULL BREEZEBLOCK TRACKLIST

[03:20 – 04:09] – The Beatles — Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise)

[03:53 – 04:53] – Hardnoise — Untitled (Instrumental)

[04:09 – 04:09] – DJ Q-Bert — Toasted Marshmallow Breaks (Side B) [T La Rock & Jazzy Jay — It’s Yours] [sample]

[04:44 – 05:17] – The Chemical Brothers — Chemical Beats

[04:53 – 04:53] – Double Dee & Steinski — The Payoff Mix [Malcolm McLaren — Jive My Baby] [sample]

[05:01 – 05:10] – Ultramagnetic MC’s — Kool Keith Housing Things

[05:18 – 05:50] – Lightnin’ Rod — Sport

[05:50 – 06:05] – La Pregunta — Shangri La

[06:06 – 07:14] – Ultramagnetic MC’s — Give The Drummer Some

[07:15 – 08:10] – Time Zone — Wildstyle (Special New Mix) (Instrumental)

[08:09 – 09:51] – Time Zone — Wildstyle (Special New Mix)

[09:51 – 09:52] – Time Zone — Wildstyle (Special New Mix) (Instrumental) [sample]

[09:53 – 10:02] – Bomb The Bass — Bug Powder Dust (The Chemical Brothers Remix) [sample]

[09:55 – 13:32] – Bomb The Bass — Bug Powder Dust

[13:30 – 14:09] – Grandmaster Melle Mel & The Furious Five — Pump Me Up (Instrumental)

[13:51 – 13:51] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [sample]

[13:51 – 14:55] – The Charlatans — How High

[14:10 – 14:28] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side B) [sample]

[14:27 – 14:37] – DJ Q-Bert — Toasted Marshmallow Breaks (Side A) [sample]

[14:37 – 14:51] – Schoolly-D – P.S.K. What Does It Mean? [sample]

[14:53 – 14:58] – Mix Master Mike — Unidentifried Funk Octopus Presents Eardrum Medicine (Side B) [sample]

[14:58 – 15:48] – Ramsey Lewis — Mighty Quinn (Quinn The Eskimo) [sample]

[15:40 – 16:49] – TheProdi.gy — Poison

[15:53 – 15:53] – The B-Boys — Rock The House [sample]

[16:31 – 16:58] – Ramsey Lewis — Mighty Quinn (Quinn The Eskimo) [sample]

[16:49 – 16:49] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [sample]

[16:49 – 16:49] – All Souvenirs – Are Here

[16:53 – 16:58] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [AC/DC — Flick Of The Switch] [sample]

[16:58 – 17:25] – Mix Master Mike — Unidentifried Funk Octopus Presents Eardrum Medicine (Side B) [sample]

[17:04 – 20:21] – Babe Ruth — The Mexican

[20:01 – 20:23] – The B-Boys — Rock The House

[20:24 – 20:28] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [T La Rock — Back To Burn] [sample]

[20:27 – 21:03] – The Chemical Brothers — (The Best Part Of) Breaking Up

[20:30 – 20:56] – Davy DMX — One For The Treble (Fresh) (Bonus Beats) [sample]

[20:47 – 20:48] – Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force — Renegades Of Funk [sample]

[20:58 – 22:26] – Word Of Mouth & DJ Cheese — King Kut

[21:03 – 21:07] – Michael Viner’s Incredible Bongo Band — Apache [sample]

[22:06 – 22:44] – Gaz — Sing Sing

[22:42 – 22:58] – Dynamic Corvettes — Funky Music Is The Thing (Part 2) [sample]

[22:59 – 22:59] – Uncle Louie — I Like Funky Music [sample]

[23:01 – 23:19] – Rueben Wilson — Got To Get Your Own

[23:21 – 24:55] – DJ Mink — Hey! Hey! Can U Relate (Hard Instrumental)

[24:31 – 27:17] – The KLF — What Time Is Love

[26:00 – 27:16] – Frankie Bones — Funky Acid Makossa (The Apachies Acid Beats) [sample]

[27:16 – 28:07] – Frankie Bones — Shafted Off

[27:51 – 30:31] – Frankie Bones — And The Break Goes Again (Italia Mix)

[29:20 – 32:05] – Meat Beat Manifesto — Radio Babylon

[32:03 – 32:10] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [Marley Marl featuring MC Shan — Marley Marl Scratch] [sample]

[32:10 – 32:10] – The Magic Disco Machine — Scratchin’ [sample]

[32:10 – 32:23] – Kool & The Gang — Music Is The Message [sample]

[32:24 – 32:26] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [Marley Marl featuring MC Shan — Marley Marl Scratch] [sample]

[32:26 – 32:28] – Herbie Hancock — Rockit [sample]

[32:28 – 32:30] – TheProdi.gy — Smack My Bitch Up [sample]

[32:30 – 32:32] – Public Enemy — Public Enemy No. 1 [sample]

[32:32 – 32:34] – Beastie Boys — The New Style [sample]

[32:34 – 32:36] – The 45 King — The 900 Number [sample]

[32:37 – 32:38] – TheProdi.gy — Molotov Bitch [sample]

[32:39 – 33:31] – Beastie Boys — The New Style

[32:43 – 34:19] – Propellerheads — Spybreak!

[34:19 – 34:21] – Word Of Mouth & DJ Cheese — King Kut (Latin Rascals Instrumental) [sample]

[34:21 – 34:37] – DJ Swamp — Swamp Breaks — C1 Untitled [sample]

[34:33 – 34:49] – Mix Master Mike — Unidentifried Funk Octopus Presents Eardrum Medicine (Side B) [sample]

[34:38 – 37:40] – Sex Pistols — New York

[37:32 – 37:51] – Fatboy Slim — Punk To Funk [sample]

[37:36 – 37:53] – Mix Master Mike — Unidentifried Funk Octopus Presents Eardrum Medicine (Side B) [sample]

[37:54 – 40:14] – Medicine — I’m Sick

[40:15 – 40:15] – DJ Q-Bert — Toasted Marshmallow Breaks (Side B) [The KLF — Last Train To Trancentral (Live From The Lost Continent)] [sample]

[40:25 – 40:43] – D.St. — The Home Of Hip Hop

[41:37 – 41:39] – D.St. — The Home Of Hip Hop [sample]

[42:17 – 42:36] – Beastie Boys — Time To Get Ill

[42:36 – 42:51] – Barry White — I’m Gonna Love You Just A Little More Baby [sample]

[42:36 – 42:52] – Psychedelic Skratch Bastards — Battle Breaks (Side A) [sample]

[42:50 – 43:11] – Public Enemy — Public Enemy No. 1

[42:55 – 43:14] – Tommy Roe — L.L. Bonus Beats #2 [sample]

[43:12 – 43:13] – All The People featuring Robert Moore — Cramp Your Style [sample]

[43:14 – 44:15] – Fred Wesley & The JB’s — Blow Your Head

[43:24 – 43:23] – DJ Q-Bert — Toasted Marshmallow Breaks (Side B) [Dimples D. — Sucker D.J.’s (I Will Survive) (Suckapella)] [sample]

[43:24 – 43:28] – DJ Q-Bert — Toasted Marshmallow Breaks (Side B) [Malcolm McLaren — Buffalo Gals] [sample]

[43:38 – 43:56] – Public Enemy — Public Enemy No. 1

[43:57 – 45:08] – T La Rock — Breaking Bells (Dub)

[44:27 – 44:28] – D.St. — The Home Of Hip Hop [sample]

[44:29 – 44:43] – DJ Q-Bert — Toasted Marshmallow Breaks (Side B) [Divine Sounds – Do Or Die Bed Sty] [sample]

[45:09 – 46:07] – T La Rock — Breaking Bells (Club)

[45:51 – 46:42] – LL Cool J — Get Down

[46:07 – 46:34] – Fausto Papetti — Love’s Theme [sample]

[46:43 – 46:45] – Digital Underground — The Humpty Dance [sample]

[46:44 – 47:17] – Uptown — Dope On Plastic (Dubstrumental)

[46:56 – 47:17] – Digital Underground — The Humpty Dance [sample]

[47:17 – 48:11] – Faust – Canyon Hill

[47:17 – 48:11] – Uptown — Dope On Plastic

[48:11 – 48:29] – Uptown — Dope On Plastic (Dubstrumental)

[48:19 – 50:02] – Coldcut — Beats + Pieces (Mo’ Bass Remix)

[49:55 – 51:09] – London Funk Allstars — Sure Shot

[51:01 – 52:11] – West Street Mob — Break Dance-Electric Boogie

[52:11 – 52:11] – T La Rock — Breakdown [sample]

[52:11 – 52:16] – Michael Viner’s Incredible Bongo Band — Apache [sample]

[52:14 – 52:15] – Bram Tchaikovsky — Whiskey And Wine [sample]

[52:16 – 52:27] – Hijack — Doomsday Of Rap (Instrumental)

[52:18 – 52:19] – Michael Viner’s Incredible Bongo Band — Apache [sample]

[52:27 – 52:27] – Word Of Mouth & DJ Cheese — King Kut [sample]

[52:28 – 53:00] – Hijack — Doomsday Of Rap

[52:31 – 52:33] – Public Enemy — Countdown To Armageddon [sample]

[52:32 – 52:35] – James Brown — The Payback Mix (Keep On Doing What You’re Doing But Make It Funky) [sample]

[53:00 – 53:15] – Mix Master Mike — Unidentifried Funk Octopus Presents Eardrum Medicine (Side B) [Kurtis Blow — Do The Do] [sample]

[53:00 – 54:34] – Renegade Soundwave — Ozone Breakdown

[54:21 – 54:34] – The Beginning Of The End — Funky Nassau (Part 2) [sample]

[54:33 – 54:33] – The Beginning Of The End — Funky Nassau (Part 1) [sample]

[54:34 – 54:36] – Bram Tchaikovsky — Whiskey And Wine [sample]

[54:36 – 55:16] – The Beginning Of The End — Funky Nassau (Part 1)

[55:16 – 55:27] – The Beginning Of The End — Funky Nassau (Part 2)

[55:28 – 55:32] – The Beginning Of The End — Funky Nassau (Part 1) [sample]

[55:32 – 58:24] – The Jimmy Castor Bunch — It’s Just Begun

By the way, a funny fact: in the original broadcast towards the end of the mix, you could clearly hear clicks from a computer mouse! This can be explained by the likelihood that in the BBC Radio 1 studio, Mary was sitting at a computer and turned on the microphone to say a few words at the end of the show. However, she probably decided not to interrupt the mix with her voice in the middle of the tune and forgot to turn the microphone off again.

There was also a phone interview with Liam and Mary Anne Hobbs at the very beginning of the show’s airing, you can read what they talked about here: https://theprodigy.info/articles/dc-interview.html

As a result, three different edits of the mix were done!

- The first one was aired on Radio One on October 12, 1998.

- The second edit was made by Liam in November 1998. This is the only version that contains a 25-second intro where a robotic voice spells out the word “Dirtchamber”. Liam gifted this mix to Martin James on the aforementioned 2nd Edit CDr. This same version was distributed on incredibly rare promos with the label “Masterpiece Mastering” mentioned on the insert. Only 25 of these promo discs were produced, all individually numbered. There’s also a promo disc called ’20 Minute Outake’ from the German label Intercord, featuring a 20-minute excerpt of this second edit of the mix.

- The third and final version is the well-known Dirtchamber: this is how the mix sounded after all the copyright issues were sorted out (as Liam couldn’t release the mix in its original form due to XL Recordings not being able to clear the sample rights from all the copyright owners).

Also in article dedicated to ‘Dirtchamber Sessions’ release, we’ve thoroughly sorted out the tracklists of all three mixes and identified all the differences between them. Check this out!

Headmasters: SPLIT, SIXSHOT

Donate

- Tether (USDT)

- Tether (USDT)

Donate Tether(USDT) to this address

Donate Bitcoin(BTC) to this address

Please Add coin wallet address in plugin settings panel

SBER/QIWI (RUS): 8950008190б