Electronic Punks • 30th Anniversary

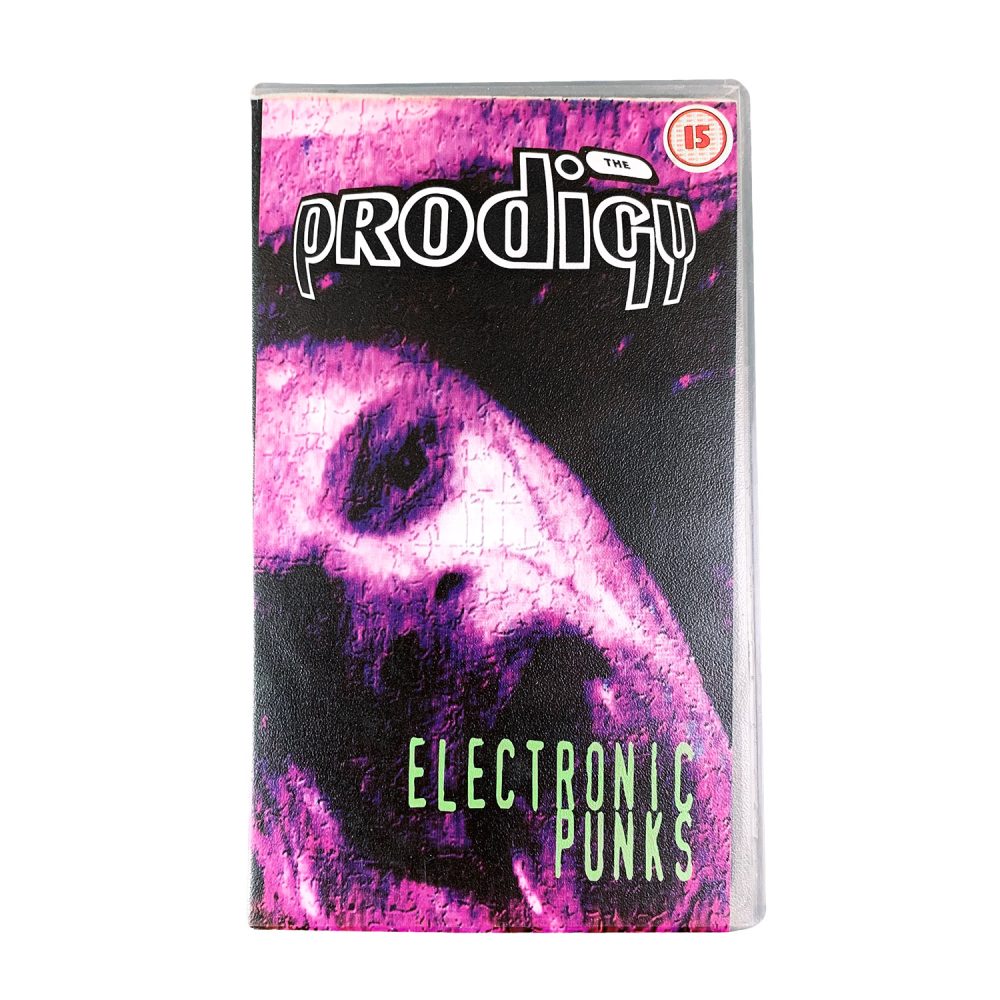

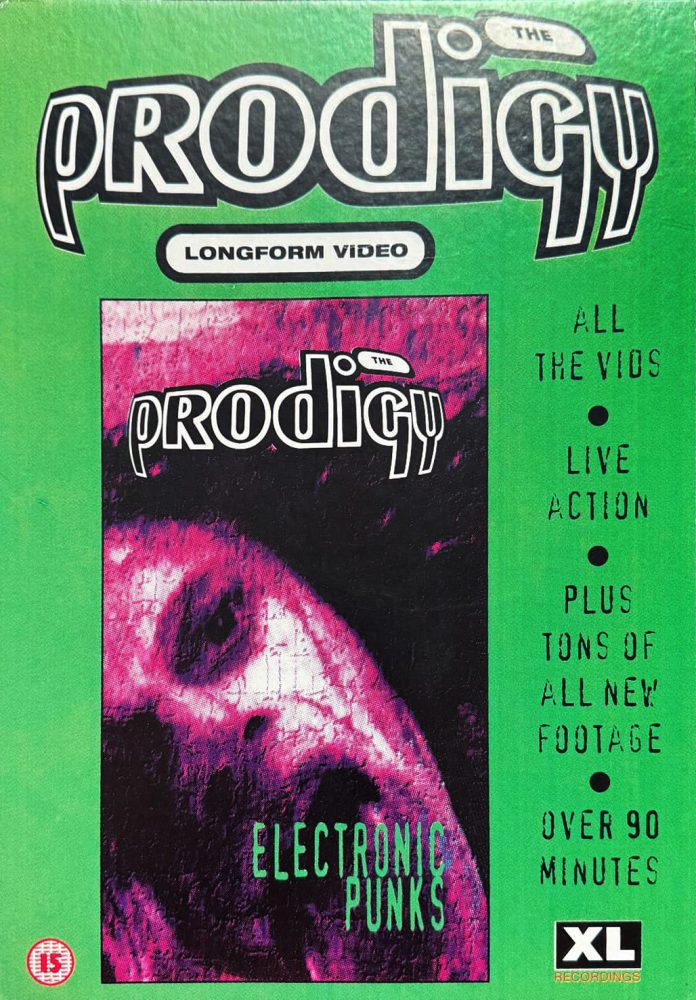

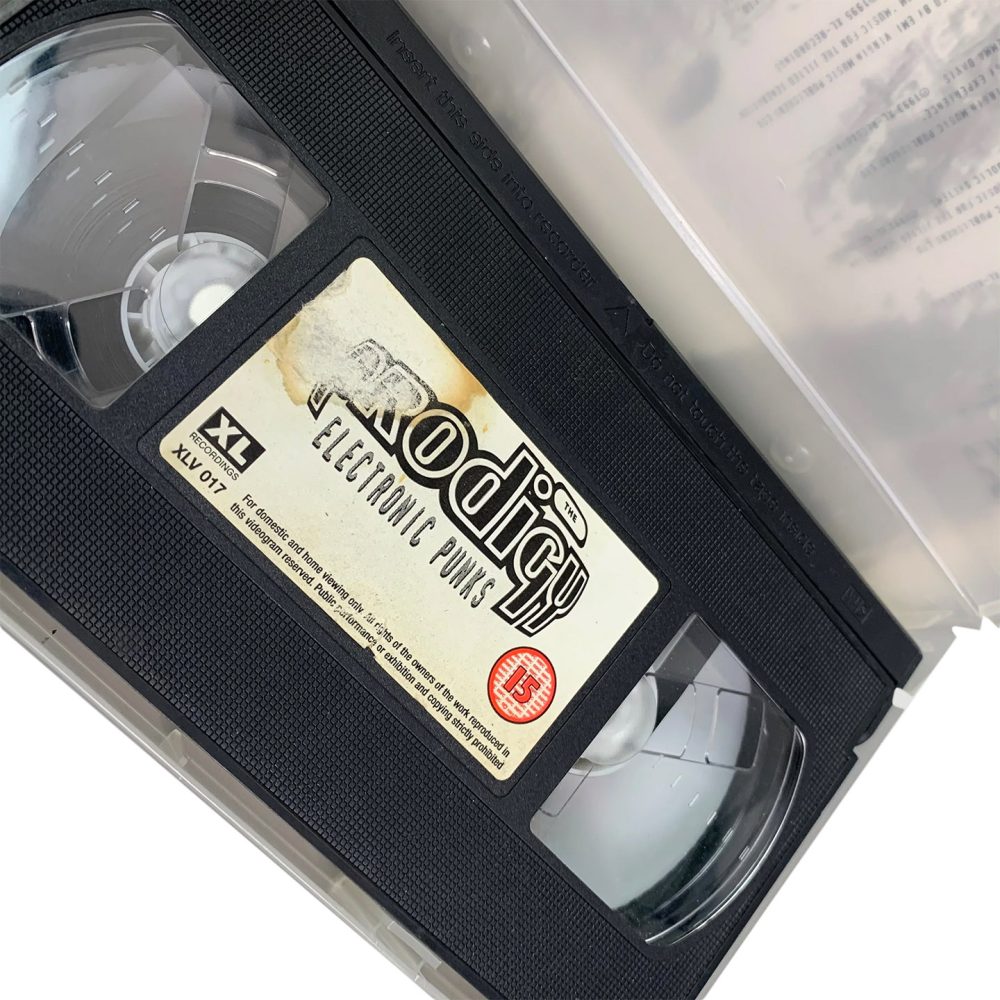

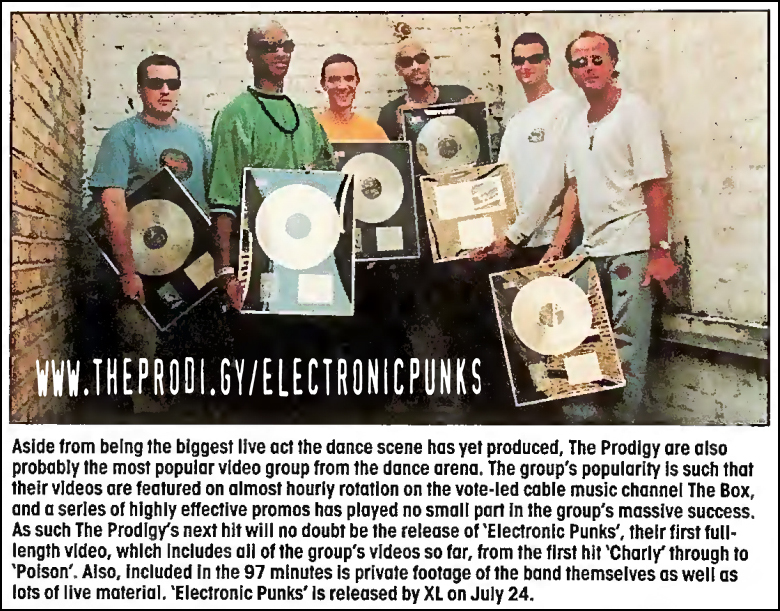

In summer 2025, ‘Electronic Punks’ — The Prodigy’s iconic VHS — turns 30. Released in July 1995, the tape has achieved legendary status among fans over the years. Yet originally, it was meant to be a simple compilation of music videos, with no extras or behind-the-scenes footage. Every addition had to be fought for, debated, and painfully approved by the label. All Souvenirs spoke to the director Mark Reynolds and several others who were directly involved in the making of ‘Electronic Punks’ to get the full story behind how it came together — and to find out once and for all: will a proper digital version ever see the light of day?

“We’re only doing it once, ask as many follow-up questions as you like. Don’t think I’ll be around for the 60th anniversary!” Mark Reynolds laughs. The director and producer of the original tape knows exactly how much this video still means to the fans — and how rough-edged its creation really was. Now, three decades later, Mark begins his story.

The idea for the VHS was first raised in December 1994. At the time Mark Reynolds was in the middle of editing the ‘Poison’ video along with Walter Stern, when XL Recordings approached him with a suggestion: would he be up for putting together The Prodigy video compilation for a future VHS release? The job was formally commissioned by the marketing department at the end of January 1995.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘I was cautious, having previously worked on a couple of adverts for the marketing department that were never released, including a TV spot for ‘Music for the Jilted Generation’ featuring the model from the album cover. When Liam caught wind of that campaign, he shut it down. He didn’t want TV ads, and I completely understood.’

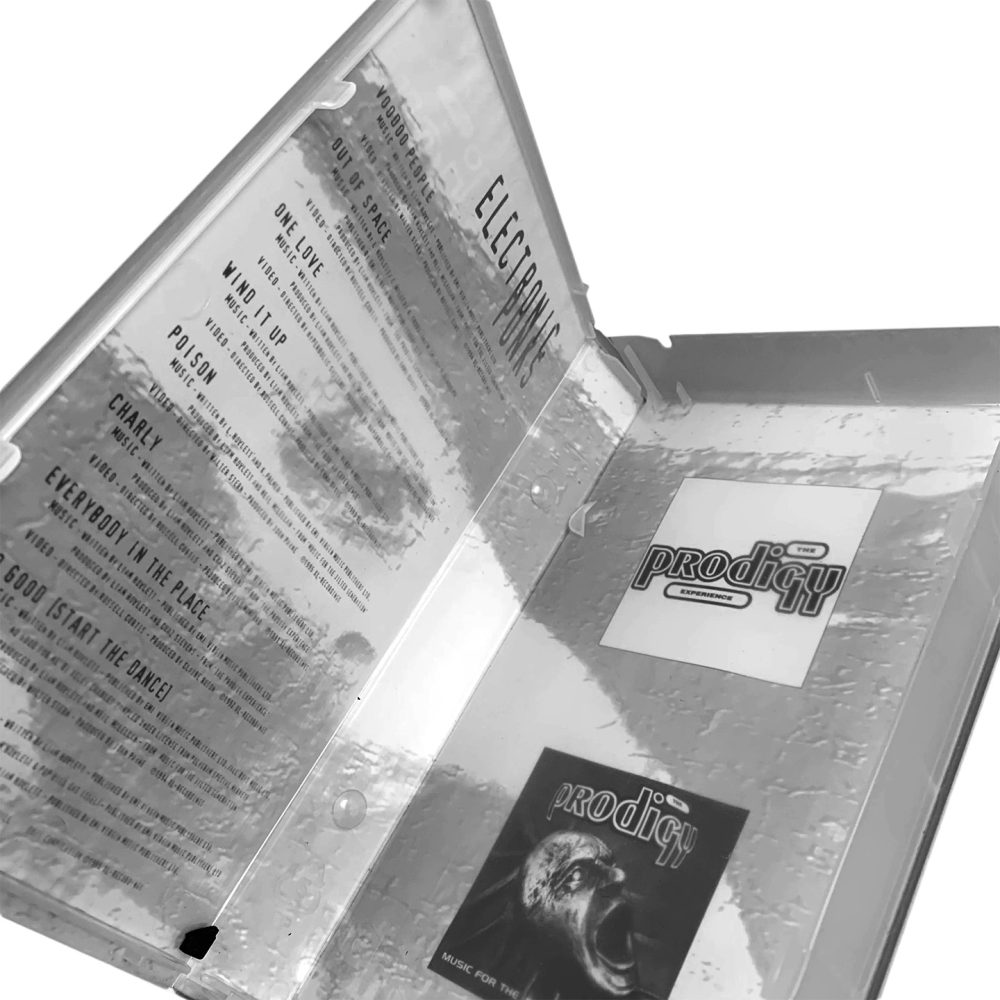

The label’s brief was straightforward: compile all the music videos in chronological order (excluding ‘Fire’), add a basic title card at the beginning reading ‘The Prodigy Videos’, and finish with a standard credits sequence. The concept clearly felt flat — most of the videos had already been released on the ‘XL Chapter One’ VHS, and it seemed likely that viewers would simply skip to the three new videos and lose interest by the time the credits rolled. ‘Not exactly thrilling’, Mark grins.

But on New Year’s Eve, something clicked during a conversation between Mark and Liam about the kind of videos they actually loved. Both of them had a deep appreciation for Nirvana’s ‘Live! Tonight! Sold Out!!’ VHS — a chaotic, intimate mashup of live footage, interviews, offcuts and nonsense. ‘I wanted to make something more like that,’ Mark recalls, ‘raw, energetic, and personal.’

Gradually unfolding the idea, Mark brought up how valuable the early footage of The Prodigy was: rough around the edges, but full of energy and character. When he asked if any of those old tapes were still available, Liam gave a cheeky laugh — turns out he had dozens of hours just sitting there.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘Do you have any of that early stuff?’ I asked. Liam laughed. ‘Yeah, I’ve got a bit.’

With Liam’s blessing, Mark looped in Mike Champion, the band’s manager at the time, to help push the idea forward. From the very beginning, Reynolds was clear on where he stood.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘I said yes to the commission fully intending not to deliver what was asked. In hindsight, that probably invited trouble, but sometimes, when your gut tells you something’s wrong, you have to go against the grain.’

A little later, a box arrived. Inside: around 40 Video8 tapes of varying length — Liam’s own archive, packed with candid recordings of the band’s earliest years. It was truly a big moment: being entrusted with that much raw, unreleased material felt like a rare window into a side of The Prodigy few people had ever seen.

Mark did what any editor in his position might — shut the world out and got to work. His flatmate was away, so he had the place to himself. Armed with a remote in one hand and a notepad in the other (plus a few ‘nice things’ to stay awake, as he puts it), he sat down and watched all 40 tapes in a single sitting. By the end, he’d filled pages of storyboards and notes, marked endless timecodes, flagged every standout moment — with his eyes practically falling out of their sockets.

Two of the clips Mark came across early on — and still remembers vividly — featured Keith doing his bodybuilder impression and, later, shouting ‘Kick my butt!’ The former eventually opened the VHS, the latter appears about 14 minutes in. Both stood out instantly when Mark first went through Liam’s tapes, and for him, they perfectly captured the raw energy he was looking for. ‘I think it was on the first tape I watched,’ he says now. ‘I clearly remember that moment — I had a bag of weed, a bit of coke, a bottle of malt whiskey, and another 39 tapes to watch!’ He laughs, then adds: ‘This is off the record of course!’ Sure it is, Mark. Sure it is.

Once the best segments were selected, Mark headed to Complete Video in Covent Garden (Slingsby Place, London) — the underground post house that would become mission control for ‘Electronic Punks’. ‘I loved that place at the time,’ Mark reflects, ‘most of it was underground with lots of tunnels. It felt a bit like the Batcave.’

Working alongside editor Simon Giblin, they began transferring the chosen footage, adding burnt-in timecodes for reference. A VHS dub was then couriered to Liam for review, so he could approve or reject each shot. ‘Altogether, we ended up with just over an hour of footage — fragments of something raw, real, and entirely theirs,’ Mark reflects.

Simon Giblin for All Souvenirs: ‘It’s hard for me to remember a great deal about the process of Mark’s projects in his basement in Crouch End, there were lots of missing passages of time in those days… If you know what I mean!’

‘Electronic Punks’ was actually one of the first long-form projects Simon worked on. When he began the actual edit, he made full use of the linear editing suite, bouncing video between disks — a process that would be much smoother with today’s non-linear editing systems. Working on U-matic also wasn’t frame-accurate, so an edit that takes less than a second today could take a minute or two. ‘Sometimes some edits were stubborn & you had to persevere longer, or leave it & come back later’, Giblin admits.

Simon Giblin for All Souvenirs: ‘Searching for shots was also a big pain in the arse, as you had to insert the correct tape, then fast forward to the correct section only to find the shot you thought might work didn’t. Some tapes could be 60 minutes or more.’

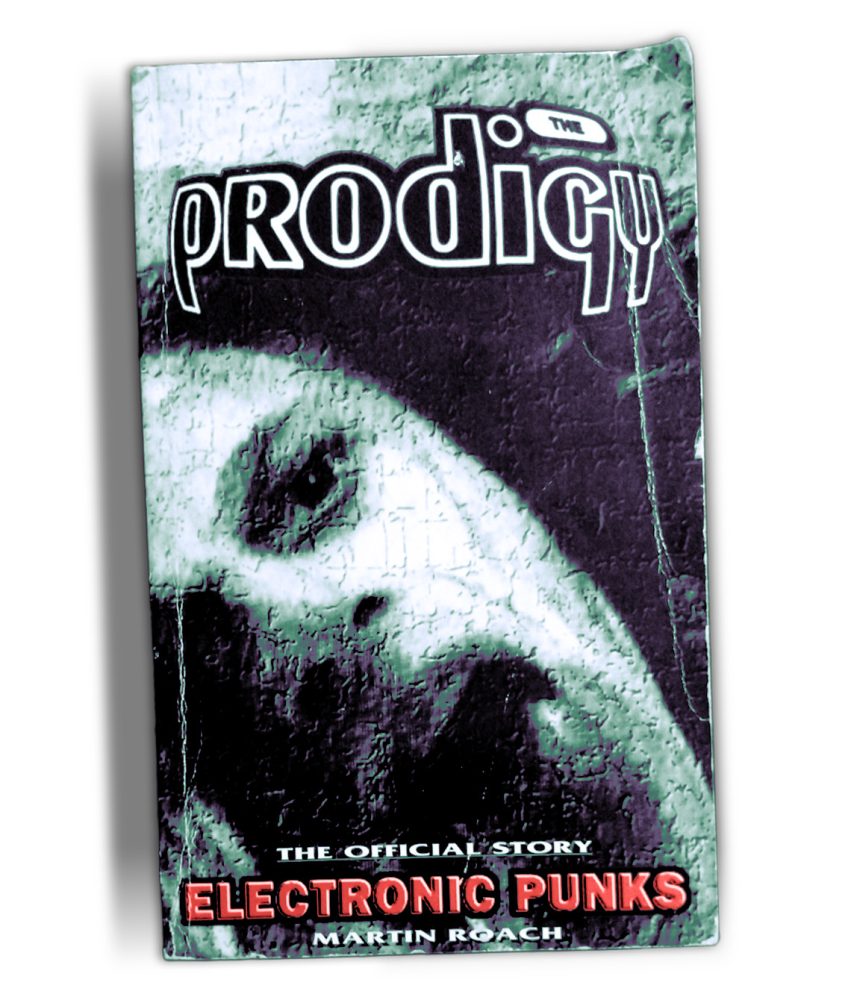

Instead of using the dull placeholder ‘The Prodigy Videos’ — as originally suggested by the label — it was decided to go with something bolder: ‘Electronic Punks’. The title had first appeared just a little while ago, in Spring 1995, as the title of Martin Roach’s official book on the band.

And it wasn’t just the name that carried over. The book’s cover, based on a single frame from the ‘No Good (Start The Dance)’ video (around the 1:37 mark), was also repurposed for the VHS. The original artwork had been treated by Sharon Thornhill — Leeroy Thornhill’s sister, who was often around the band and occasionally contributed visuals in the mid-90s. ‘It was a good image and The Prodigy chose to use it on the cover’, she told All Souvenirs years ago.

We shared the cover creation process on our Instagram.

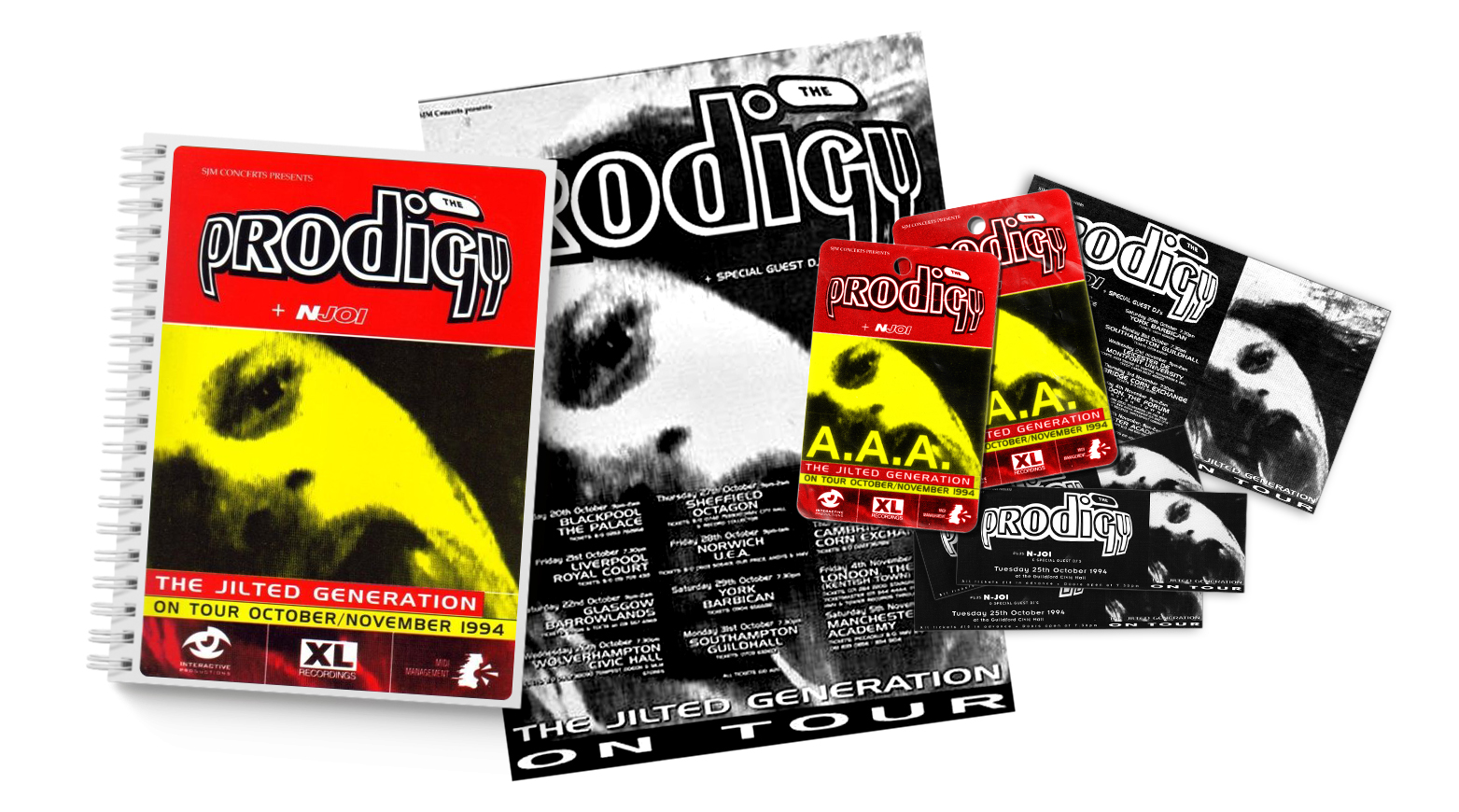

In fact, the same still from ‘No Good (Start the Dance)’ had already been used by the band as early as autumn 1994, during their October–November UK tour in support of ‘Music for the Jilted Generation’. After the new year, the image appeared again on the cover of the official book, and when it came time for the VHS release, that same artwork was tweaked once more: darker tones, more contrast, heavier look — setting the mood before the tape even began to roll.

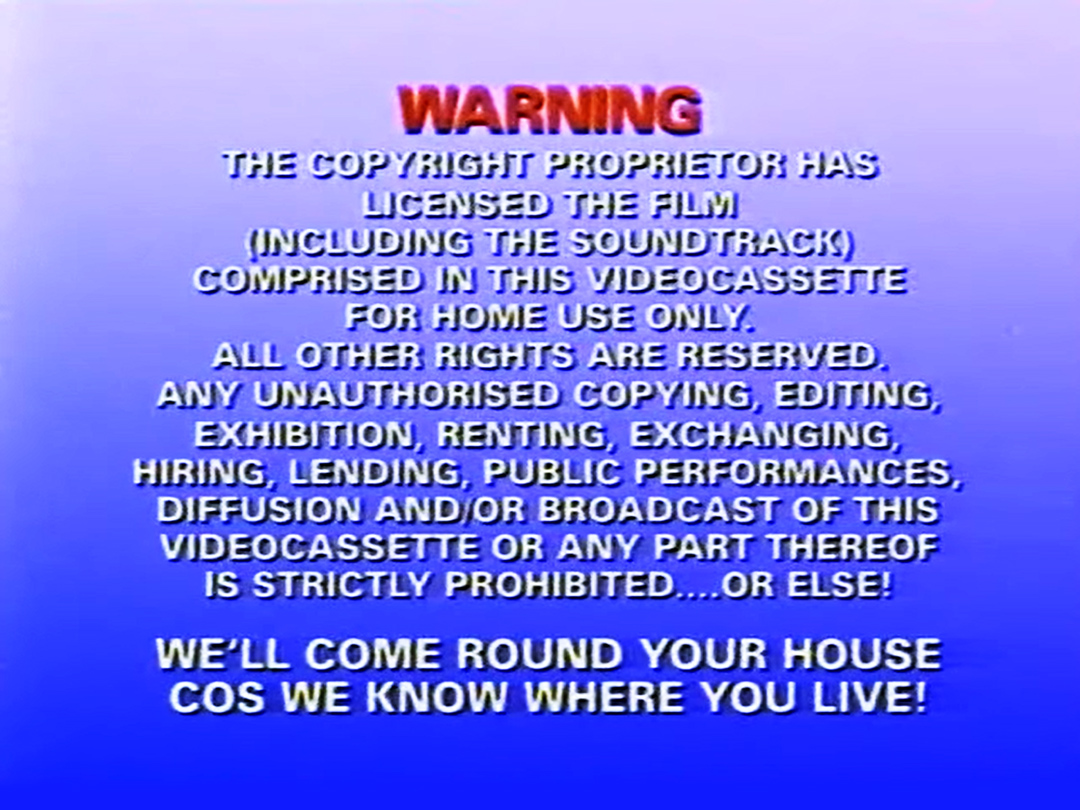

The VHS opened with a copyright warning — a bold, gradient-filled title screen closing on the line: ‘WE’LL COME ROUND YOUR HOUSE COS WE KNOW WHERE YOU LIVE!’ Maybe even a bit creepy for younger fans at the time (this writer included), but it nailed the tongue-in-cheek tone from the get-go. As Mark notes, the line was originally used in the music video for the Gutter Brothers’ track ‘The Spoiler’, which he also had directed. Mark first used that same warning screen for the Gutter Brothers’ 1994 video release, before reusing it for ‘Electronic Punks’.

While the footage was being transferred and reviewed, another piece of the puzzle was taking shape at Complete Video — the intro title sequence. According to Mark Reynolds, it had already been completed using the same logo design featured on Martin Roach’s book, along with the footage that would later appear in the final cut.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘I do remember going into the rostrum camera room and having a play, as I quite often did at Complete Video.’

Mark had originally designed the opening titles himself: a trained graphic designer, he wasn’t planning to hand off the sequence to anyone else — but at the very last minute, XL’s video commissioner informed him that the band’s logo had changed, which meant the entire sequence had to be remade. ‘For me the ant logo was better and fitted the video perfectly,’ Reynolds adds. With the deadline looming and a mountain of editing left to do, he and Simon Giblin brought in extra help.

Simon suggested that junior assistant Mark Warbrook could step in to rebuild the sequence under guidance — fresh out of college, he was also working at Complete Video. ‘We had so much work to do, we had to find someone else to redo the intro,’ Reynolds recalls. Warbrook notes that ‘Electronic Punks’ was his first job in television graphics, having started as a runner at Complete and says it was one of the projects that helped kick-start his career.

Mark Warbrook animated the ant logo using fragments of the original footage and applied animation to parts of the logo with the help of a rostrum camera. The sequence was created using a machine called the Harriet Paintbox by Quantel. This was before the team had access to Macs, as Photoshop was only just emerging. Warbrook produced a few alternate versions, which were sent to Simon Giblin on D1 tape (as was standard at the time). Reynolds reviewed the options, picked one, made a few final adjustments, and completed the sequence alongside Giblin in the online suite. All in all, the VFX might seem a bit naive by today’s standards, but at the time they nailed the spirit of the era — and it still looks cool in its own way.

Given that Mark Reynolds knew from the start he wouldn’t deliver what the label originally asked for, the project quickly became a massive pain in the arse for marketing department. It was a hell of a fight to get Mark’s concept through — months of back-and-forths, arguments, and pushback. ‘There’s almost half a book you could write about the making of that video that no one at the record company wanted!’ Reynolds chuckles. ‘I still remember after all these years being screamed at “You and Liam are just making a money losing exercise! No one’s going to want to see this thing!”’

Mark vaguely recalls that the original budget offered for the project was just £2,700 — enough to string together the music videos in chronological order, slap on a basic title like ‘The Videos’, and add a set of closing credits. But once the scope of ‘Electronic Punks’ began to grow, he put in a request for a 5x larger budget. Still a modest sum, considering the finished film would run over 90 minutes. Reynolds was basically told to fuck off. Despite the pushback, Mark decided to make the video anyway. There were plenty of clashes with the marketing department along the way, but Mike Champion, true to his name, stepped in as the project’s ‘Champion Defender’.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘One incident that still makes me laugh happened near the end of the documentary’s production. The marketing team insisted I bleep out all the swear words in the video because they wanted to sell it in Woolworths — with a child-friendly classification! This time, I didn’t need Mike’s backup. I just told them, “No way. Not happening. You’ll have to find someone else to make your video — and you’re not using anything of mine. I’ll even give you your money back.” Can you imagine “Their Law” with bleeps all the way through it? Absolutely ridiculous.’

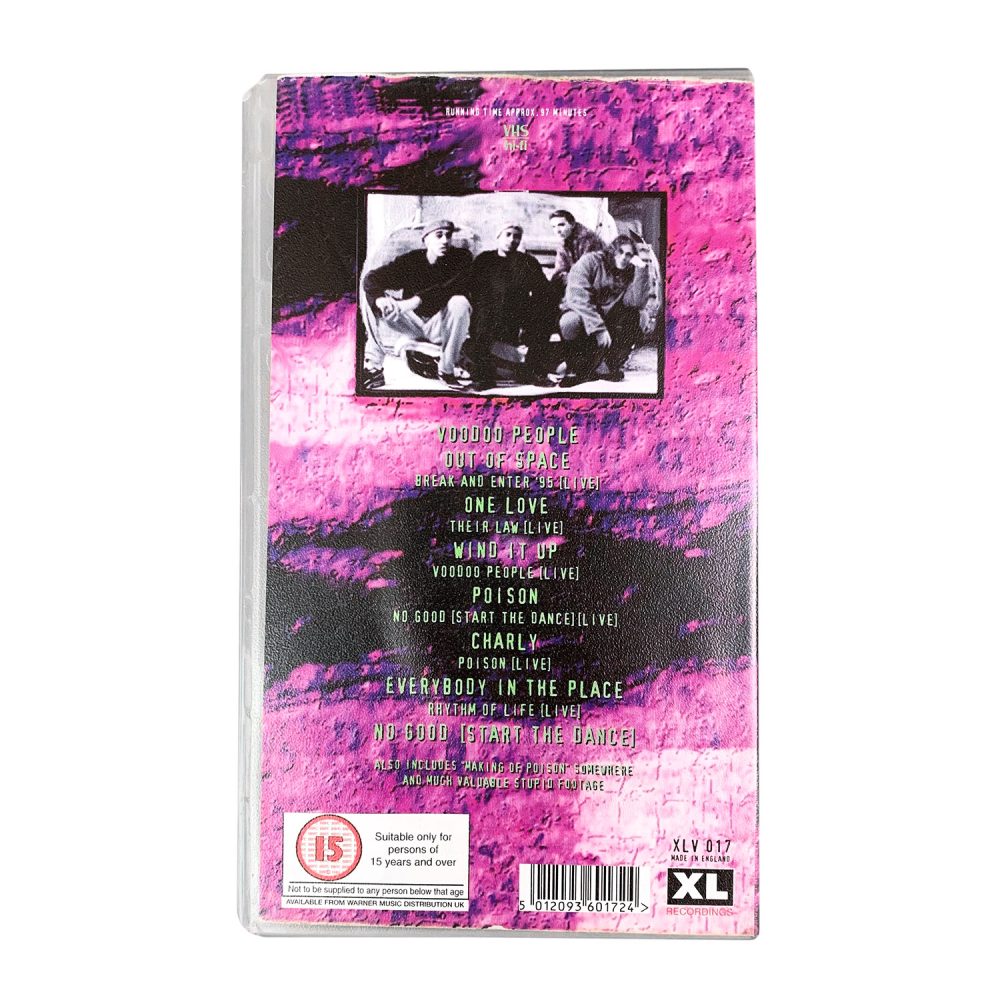

Rather than follow the XL Recordings’ suggestion of a flat chronological compilation, Mark decided to approach the edit like he would a portfolio or mixtape — with rhythm, flow, and emotional impact in mind. He opened with ‘Voodoo People’, whose cinematic intro made it the perfect beginning, anchored the middle with ‘Poison’, and closed with ‘No Good (Start the Dance)’ — the kind of track that sticks in your head long after the credits roll. In between the videos, Reynolds spliced in bursts of live recordings and handpicked backstage footage he and Liam had selected together.

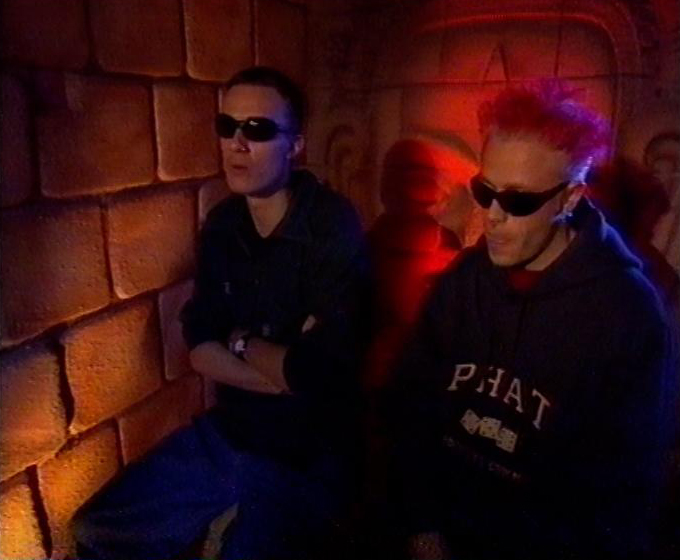

While most of the pre-1995 footage came from Liam’s archive, additional footage was shot by Mark himself as the project evolved. He made a conscious effort to keep things low-key and natural — more like a mate filming his mates than a polished production. ‘The moment you bring in lights and a sound crew, the atmosphere shifts,’ he later said to All Souvenirs. ‘It becomes less personal, more staged. And that wasn’t what we were after.’

Part of what made those early years so special was that scrappy, human quality. It felt like the band was still figuring it all out as they went — and that rawness was exactly what made it so compelling.

From Mark’s own footage, four show excerpts from the Poison Tour made it onto the final tape: Manchester’s Apollo (March 17), De Montfort Hall in Leicester (March 18), Town & Country Club in Leeds (March 21), and Brighton Centre (March 24).

Simon Giblin for All Souvenirs: ‘The fun part for me was cutting the live performances to give even just a little feel of the live Prodigy experience, especially when we had footage from angles no one would ever see, thanks to Mark climbing above the stage in Leeds and hanging off the lighting rig during “Rhythm of Life”.’

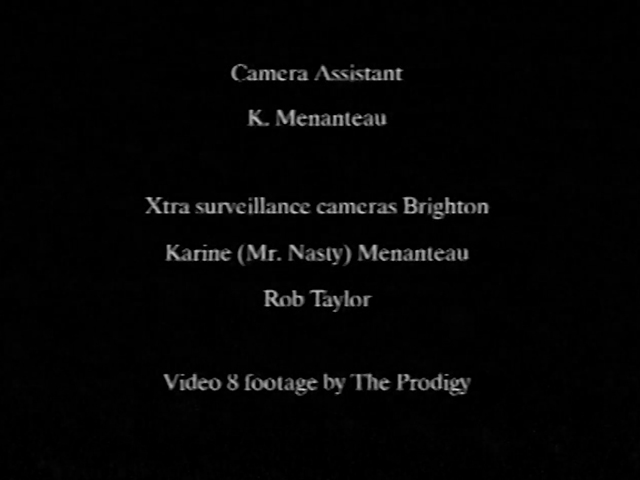

At first, it was expected to use only brief fragments — just quick bursts to break things up. But the footage held up surprisingly well, both visually and sonically, even though all of the audio came directly from Mark’s camera mic. There were no soundboard recordings, no dedicated sound crew — and in fact, the end credits openly state: ‘Live bootleg Hi8 footage’ and ‘Xtra surveillance cameras Brighton’. Basically, the biggest challenge from the start was figuring out how to film the live footage without blowing the budget.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘We had no budget to do any extra stuff, so it was coming out of my pocket. I had a wish list of things I wanted for the video, but I literally had to keep crossing things off. [The final tape] sounded great though, had a warm feel to it.’

At one point, Mark Reynolds and the team had actually assembled a full cut of the video featuring interviews throughout — but Liam felt it was leaning too much into traditional documentary territory. In the end, nearly all of those interview clips were scrapped, with only one or two quick moments left in. Looking back, Mark admits Liam was right, but points out that with hindsight, they might’ve kept the audio and layered it over live or backstage footage instead of cutting away to talking heads.

Simon Giblin for All Souvenirs: ‘Liam came round one day. I think Mark had to work on a commercial, as he was running low on cash due to the many weeks we were editing all the footage together. I do remember Liam turned up in the coolest VW camper van, music blasting out of the windows, and parked right in front of the flat’

Simon recalled how he would often spend nights in the basement, going through footage, before heading off to his day job at Complete Video — only to return in the evenings to try out different ideas in the edit suite: conforming, onlining, and experimenting with the material. Despite the heavy workload, he credits the experience as instrumental in kick-starting his career. ‘Best way to learn is by having a proper project to work on’, Giblin points out.

Simon Giblin for All Souvenirs: ‘One thing I can never forget is Mark cooking all of the time we worked together. I’d be editing downstairs for hours, and the smell would be drifting down into the basement. Then we’d take a break and eat outside in the garden. I can still remember a pork casserole marinading for a day or so — scrumptious. Yorkshire Puddings were a weekly event. If I had a business card in those days, it would read “Will work for food”. And then the never-ending supply of evil spirits entombed in Mark’s freezer! Also, he kept the Irish coffees flowing in the evening. Oh, and he had Sky! The only place I could watch the Simpsons’

Dubbing editor Ollie Usher handled the final audio mix, working his post-production magic in the audio suite. He did everything he could to make Mark’s already solid on-camera recordings sound as good as possible — and considering the source material, the end result was surprisingly strong.

Ollie Usher for All Souvenirs: ‘Electronic Punks was probably the first big project I worked on. I’d not long been promoted to audio engineer. The industry had just completed the transition phase from analog tape digital audio workstations.’

Ollie Usher worked on the entire project using an AMS Audiofile, backing everything up each night to DAT — with every clip being laid off in real time. ‘Needless to say I didn’t really sleep for the two weeks we worked on it’, Ollie chuckles. The setup had significant limitations by today’s standards: early digital audio systems offered only eight tracks, a far cry from the virtually unlimited capabilities of modern Pro Tools. To get around this, a second studio was slaved to the main one, effectively doubling the capacity to sixteen tracks. Dialogue and spot effects were run from the main room, while the music came from the slave studio located a hundred feet down the corridor. ‘Very annoying if the slave machine dropped out of sync,’ Ollie adds with a smile.

Ollie Usher for All Souvenirs: ‘It was just too exciting to care though, we pushed through because we all loved the project not least of all having a good reason to listen to music over and over on massive fuck off speakers.’

Mixing was done in a semi automated SSL G-Series mixing desk. Only fader moves were recordable so eq and compression was fixed as you set it per track. Those were the days when you really did need a 64 track £500,000 desk.

Ollie Usher for All Souvenirs: ‘I mentioned tiredness. I remember one night where Mark Reynolds and I were the only ones left working in the studio. Midnight came and went, then it was soon 2am — next thing we knew, it was 5am. We both had no sense of the passage of time from about 2 to 5am, we’d lost 3 hours. The only way I can make sense of it to this day is that we were both so knackered, we’d fallen asleep at the same time and woken up at the same time. That “Voodoo People” track is, in more ways than one, a powerful fucking tune!’

Once the audio was complete, Reynolds mastered the project to digital tape — his preferred format for preserving quality. He had hoped this version would be used for the VHS duplication, but the label pushed back, saying it would add a few extra pence to each copy. In the end, the tapes were made from a standard Betacam master instead. The quality drop was hard to ignore. ‘I couldn’t watch it for years after — so disappointing,’ Mark admits.

Alongside the flood of early camcorder footage and behind-the-scenes stuff, ‘Electronic Punks’ also marked the quiet debut of two previously unheard cuts. The first was an early demo version of ‘Molotov Bitch’ (titled ‘Come Correct’ at the time) — a track that wouldn’t see an official release until ‘Firestarter’ single dropped in March 1996, nearly eight months later. The second was a raw, live-only track called ‘Jungle Beats’, built around a ‘We Eat Rhythm’ sample by The Last Poets.

‘Jungle Beats’ opened the compilation, playing behind the intro’s legal disclaimer, while both tracks played back-to-back during the end credits. ‘I asked Liam for some music for the end credits, he sent me a DAT which I still have!’ Mark grins.

A pretty wild move, considering The Prodigy were already well on their way to global fame, and XL Recordings was known for watching the budget like hawks — down to the last pence. And yet here they were, casually dropping two brand new, completely unreleased tracks onto a VHS tape, with no fanfare. A total win for the fans.

Check out the full story behind ‘Jungle Beats’ / ‘We Eat Rhythm’:

theprodi.gy/weeatrhythm

‘Molotov Bitch’ demo was short enough to be used in full, while ‘Jungle Beats’ appeared in a shortened fade-out snippet running just over two minutes. ‘It seemed to work better with both tracks,’ Mark explains. ‘Sometimes you get that on end credits for films.’

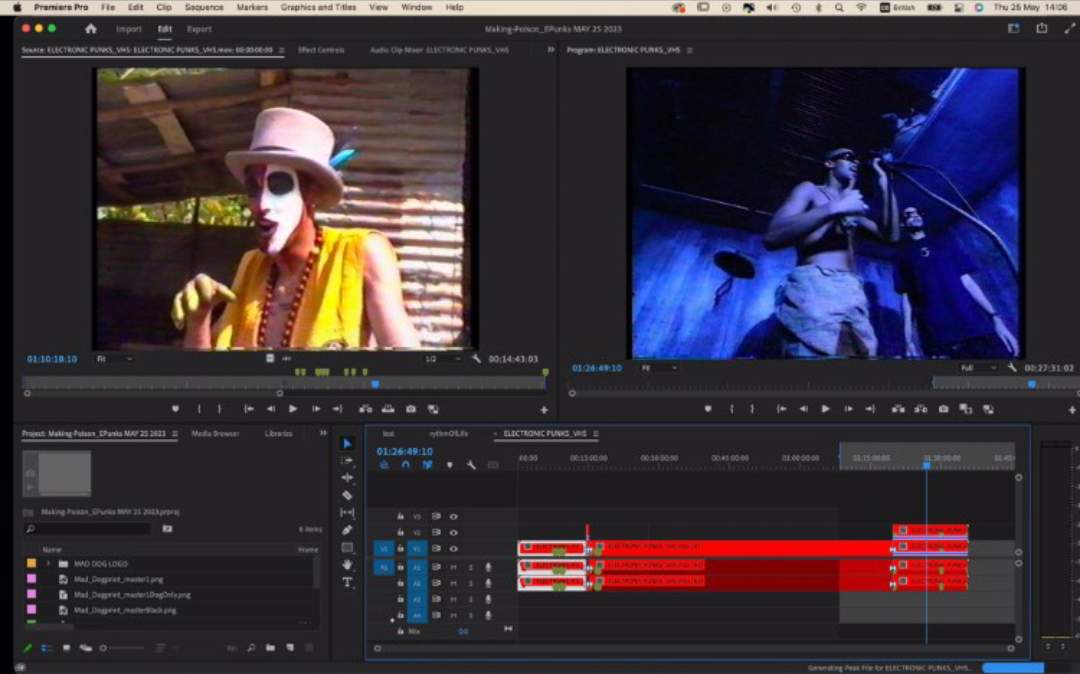

Also included among the footage Mark had shot himself was a rare behind-the-scenes mini-feature on the making of the ‘Poison’ video — a loose, grimy segment that eventually got tucked away at the very end of the tape.

The idea for it came about when director Walter Stern asked Mark Reynolds to shoot some Super 8mm and Pro Hi-8 footage during the music video’s two-day shoot, which was also being covered in 35mm. Reynolds agreed — on one condition: that he’d be allowed to film a proper behind-the-scenes documentary. He had previously collaborated with the KLF on several projects, including behind-the-scenes docs for ‘Justified Ancients of Mu Mu and America: What Time Is Love?’, and saw this as a chance to bring that same energy to The Prodigy. ‘With Poison, I wanted to create something in that same spirit,’ Mark recalls now.

Liam liked the making of ‘Poison’, but his only real hesitation came when it was time to decide what to do with it. He felt it gave away too much and might strip some of the mystique from the original video. Mark had a fix: ‘I suggested we tuck it at the very end, like one of those hidden tracks you find on certain albums. Something subtle. Some people wouldn’t even realise it was there.’

Naturally, that meant another battle with XL. ‘They were adamant: “One minute and twenty-six seconds of black after the credits? Totally unnecessary.”’ Mark pushed back, but the label was fixated on the cost: apparently, those extra seconds would add a few pence to every VHS copy.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘To be clear, it was only a couple of people at XL I felt didn’t get The Prodigy. The rest of the team were great, and I’d often pop by the office if I was in the area.’

Eventually, Mike Champion rang up and went, ‘What’s with all that black at the end?’ Mark laid it out for him — the hidden track vibe, the subtle finish — and Mike was instantly on board. ‘Brilliant,’ he said. ‘Love it. We’re doing it. Leave it to me.’

In the end, after all the battles, arguments, and endless back-and-forth, XL got their revenge by leaving Mark’s name off the VHS cover. A pretty outrageous move, considering the amount of time, money, and energy he had poured into what would ultimately become an iconic release for The Prodigy fans of all ages. You had to watch the whole video until the end before you could see the credits — and who made it.

Tucked away on the tape like a hidden gem, the making of ‘Poison’ was never released in full, and has never officially resurfaced since. A shortened six-minute cut did appear on the ‘Their Law: The Singles 1990–2005’ DVD, though. Over the past couple of years, Mark has occasionally teased the idea of properly completing and releasing the full version. Whether through Instagram posts or YouTube updates, the message was always the same: it’s coming soon. But, as it often goes, other projects and life itself seem to have taken priority.

The same goes for the long-awaited digital release of the full VHS. While fans have been asking about it for years, the reality is that it’s not up to Mark alone, but more importantly Liam and the bands management. Still, fingers crossed that someday soon at least a few rare gems from Mark’s archive — or, who knows, maybe even a proper digital master of ‘Electronic Punks’ — will finally see the light of day. Stranger things have happened. And if they do, you can bet the fans who’ve been dreaming of this moment for decades will be ready.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘From day one, we were behind schedule, so I was constantly torn — wearing the producer hat saying “No, we can’t afford that,” while the director in me was shouting “But I’ve got this great idea!” It became this internal tug-of-war between creative ambition and harsh reality. And somehow… we made it work.’

Sourced directly from Mark’s original tapes.

Headmasters: SPLIT

Additional thanks to: Mark Reynolds, Julian Paige, Simon Giblin, Ollie Usher, Mark Warbrook, Sharon Thornhill

Donate

- Tether (USDT)

Donate Tether(USDT) to this address