#Jilted30: Voodoo People · 30th Anniversary Ⅱ

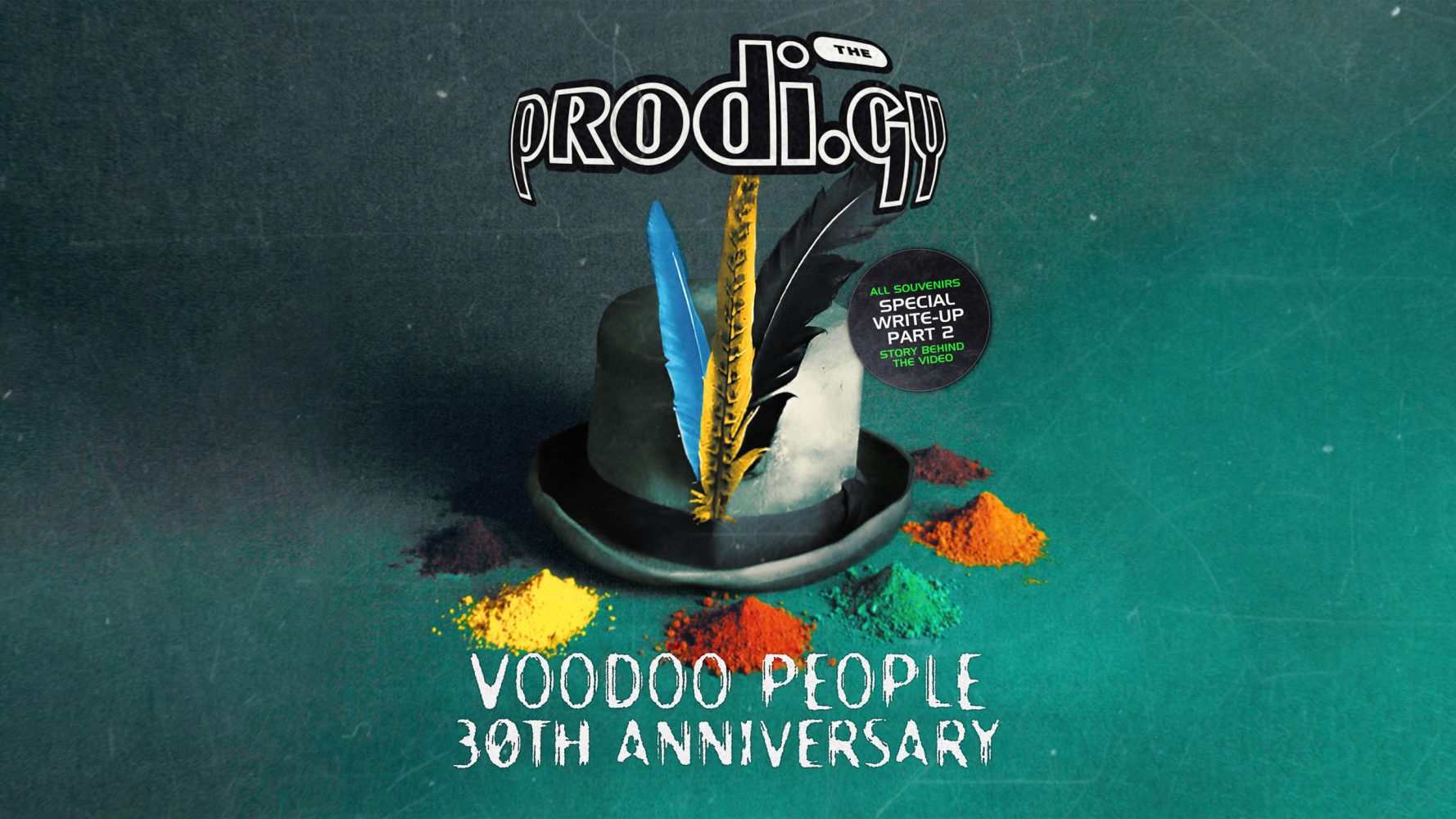

On 1 March 1995 the maxi-single Voodoo People was released in the USA on Mute Records, featuring an extended tracklist and an alternative cover. To mark this date, we will take a closer look at how it differs from the UK release, uncover the story behind its artwork, and, for the first time, provide a detailed account of the filming and editing process of the ‘Voodoo People’ music video, which had premiered six months earlier. To present the full picture, the All Souvenirs team spoke with producer Russell Curtis, editor Mark Reynolds, and designer Alison Fielding — alongside director Walter Stern, they brought to life the visuals that have captivated fans for over 30 years. We were also fortunate to get a few words from Walter himself!

After the release of Music for the Jilted Generation, The Prodigy’s popularity began to extend beyond the UK, and in the US, their releases were handled by Mute Records. In the spring of 1995, Mute released the American version of the ‘Voodoo People’ single, which featured an alternative cover.

Photographer: Stuart Haygarth

Art Direction: Alison Fielding

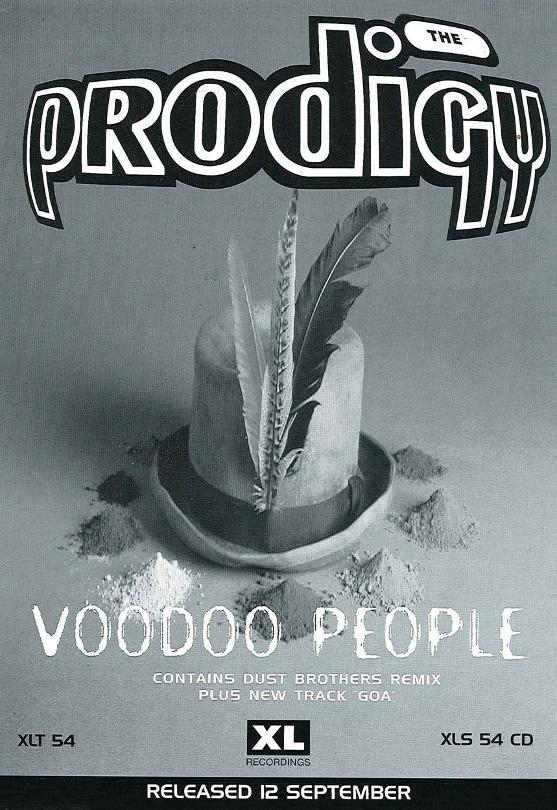

Recently, our team discovered that the sleeve designs for XL Recordings and Mute Records were created simultaneously. Alison Fielding, who was the art director at XL at the time, gave us a detailed account of how the artwork was developed.

Alison Fielding for All Souvenirs: ‘The initial idea was to use a top hat based on the James Bond villain Baron Samedi, who wore it in “Live and Let Die”. I got hold of the top hat that was used for the video and it was on the office shelf for years afterwards and taken to a few festivals by a good friend of mine! This is the top hat we chose for the cover.’

Fielding and her team decided to surround the top hat with vibrant colors to make the image as striking as possible. The paint pigments were purchased from Cornelissen, a London store that is still in operation on Great Russell Street.

Alison Fielding for All Souvenirs: ‘They had amazing names: spinal black, caput mortuum, quinacridone red! And we had to buy kilos of them to make it look impactful. The feathers were from another incredible haberdashery shop in the West End.’

However, Liam Howlett had a different idea for the cover — he wanted to create a voodoo doll that could be set on fire and melt, so on the day of the shoot, the team hastily put one together from scratch. ‘We just went out, bought a load of candles, and melted them down!’, Fielding recalls. In the end, Liam chose the melting doll as the official artwork, though Alison always preferred the top hat.

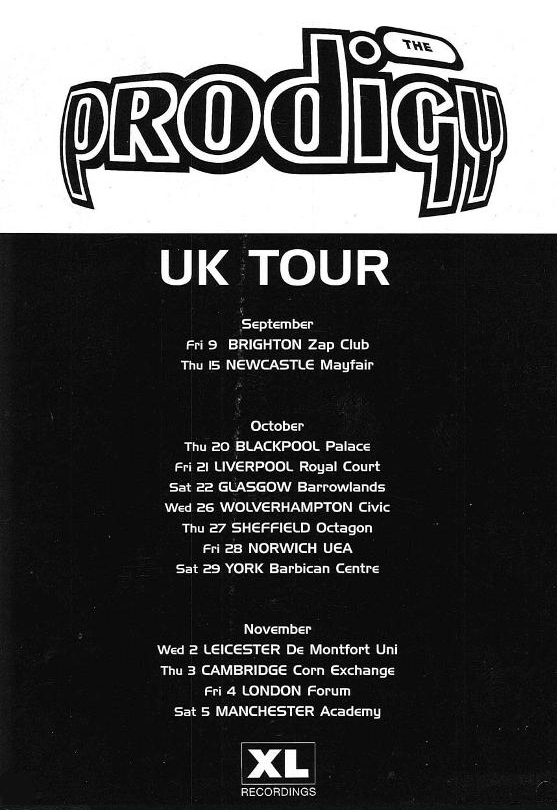

Nevertheless, in the autumn of 1994, a photograph featuring the hat was still used as promo for the upcoming XL Recordings single and was later selected as the main cover for the American release on Mute.

The photographs were taken by Stuart Haygarth, who had previously created the iconic cover image for ‘Music for the Jilted Generation’. Stuart told the All Souvenirs team that he remembers the shoot for ‘Voodoo People’ but couldn’t recall any details of the process. Most likely, it was just one of many freelance assignments he was working on at the time.

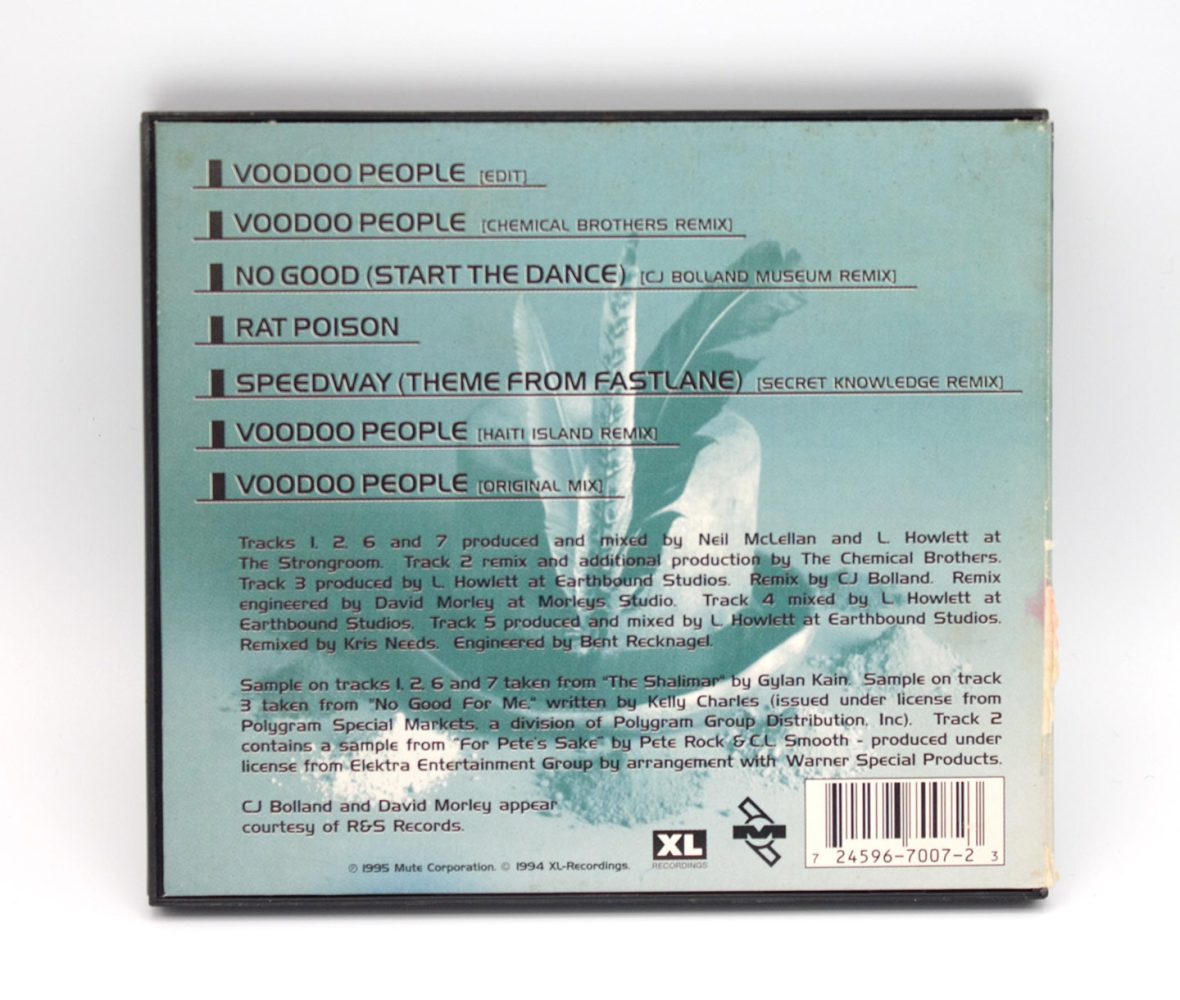

Nerd alert: a closer look at the official releases of ‘Voodoo People’ reveals some mastering differences. The original 1994 XL release of ‘Jilted’, including the original single, differs from the 1995 Mute single and the 2008 reissue ‘More Music for the Jilted Generation’. In particular, the ‘More Music…’ reissue is more compressed (perhaps not surprisingly), while the Mute version shows significant EQ changes.

Notably, this release marked the first time that a remix by Chemical Brothers was credited under their current name — in the 1994 UK release, they were still listed as Dust Brothers. By that point, the duo had begun working in the US and faced the need to change their name. According to multiple sources, Tom Rowlands and Ed Simons had originally adopted the name Dust Brothers as a tribute to the renowned Los Angeles producers behind Beastie Boys’ album ‘Paul’s Boutique’, believing they would never achieve mainstream success. However, in the beginning of 1995, the original Dust Brothers reached out to them, and to avoid legal disputes, the Chems were forced to abandon their old name.

Speaking of legal disputes, it’s worth noting that in the American release of ‘Voodoo People’, a sample from Boogie Down Productions’ track ‘Poetry’ (the line “this beat may drop but not like all the others”) was reversed — likely for the same reason, to avoid legal issues. It was not credited in the single’s sleeve, and the management seemed to hope that this approach would allow it to go unnoticed. A similar case occurred with ‘Full Throttle’: in the album version, its only vocal sample was also reversed, unlike in the single version. You can read more about this in our previous article.

- Sample: vocals (‘the beat may drop but not like all the others’)

- Sample source: Boogie Down Productions – Poetry [Criminal Minded, 1987]

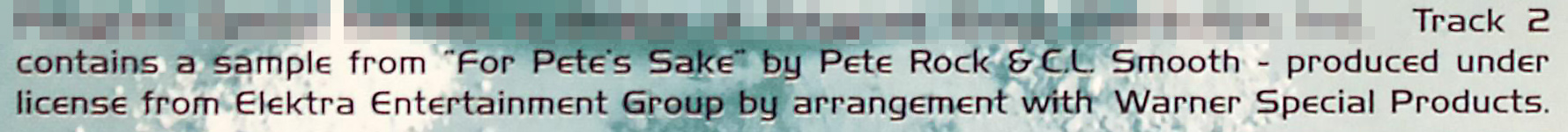

In the US, copyright laws regarding samples were already so strict at the time that for The Chemical Brothers’ remix (under this name, not The Dust Brothers), they had to officially register the sample ‘Rock the House In’, listing it in the booklet as part of ‘For Pete’s Sake’ by Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth.

Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth – For Pete’s Sake (‘Rock The House’ verse)

However, the actual sample wasn’t taken from ‘For Pete’s Sake’ at all. It came from Kenny Dope’s ‘Rock Da Haus Anna’, which, in turn, did not sample Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth’s original track! The key detail here is that in 1993, Kenny Dope used the same line, but re-recorded, while its original source was ‘For Pete’s Sake’, released a year earlier in 1992. In The Chemical Brothers’ remix, they essentially sampled one of the two versions of this re-recorded line. Nevertheless, to avoid any potential legal issues, royalties had to be paid to the original rights holders — Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth.

- Sample: vocals (‘rock the house Ann’)

- Sample source: Kenny Dope – Rock Da Haus Anna [Phat Beats – Volume 1, 1993]

Given this, it’s hardly surprising that the Boogie Down Productions / KRS-One sample in the US release was simply reversed — it was an easier solution than going through the entire clearance process.

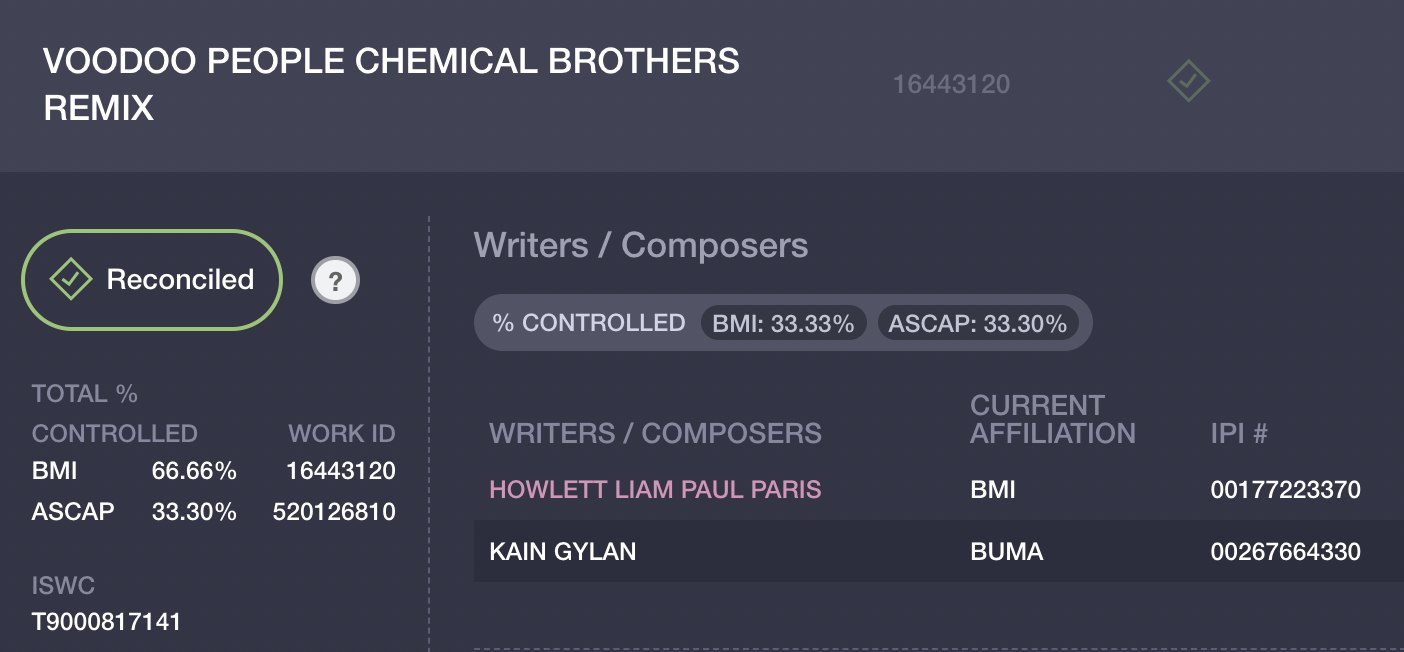

Interestingly, The Chemical Brothers’ remix was officially registered as a separate entry in PRS / BMI licensing databases, even though remixes are typically not registered as standalone works — they are considered derivative versions of the original. Moreover, the listed co-writers were exactly the same as in the original version of ‘Voodoo People’. In theory, there was no real reason to register the remix separately, except for one key factor: it was most likely added to the registry at the moment when the ‘For Pete’s Sake’ sample was included, and for some time, royalties were even officially paid.

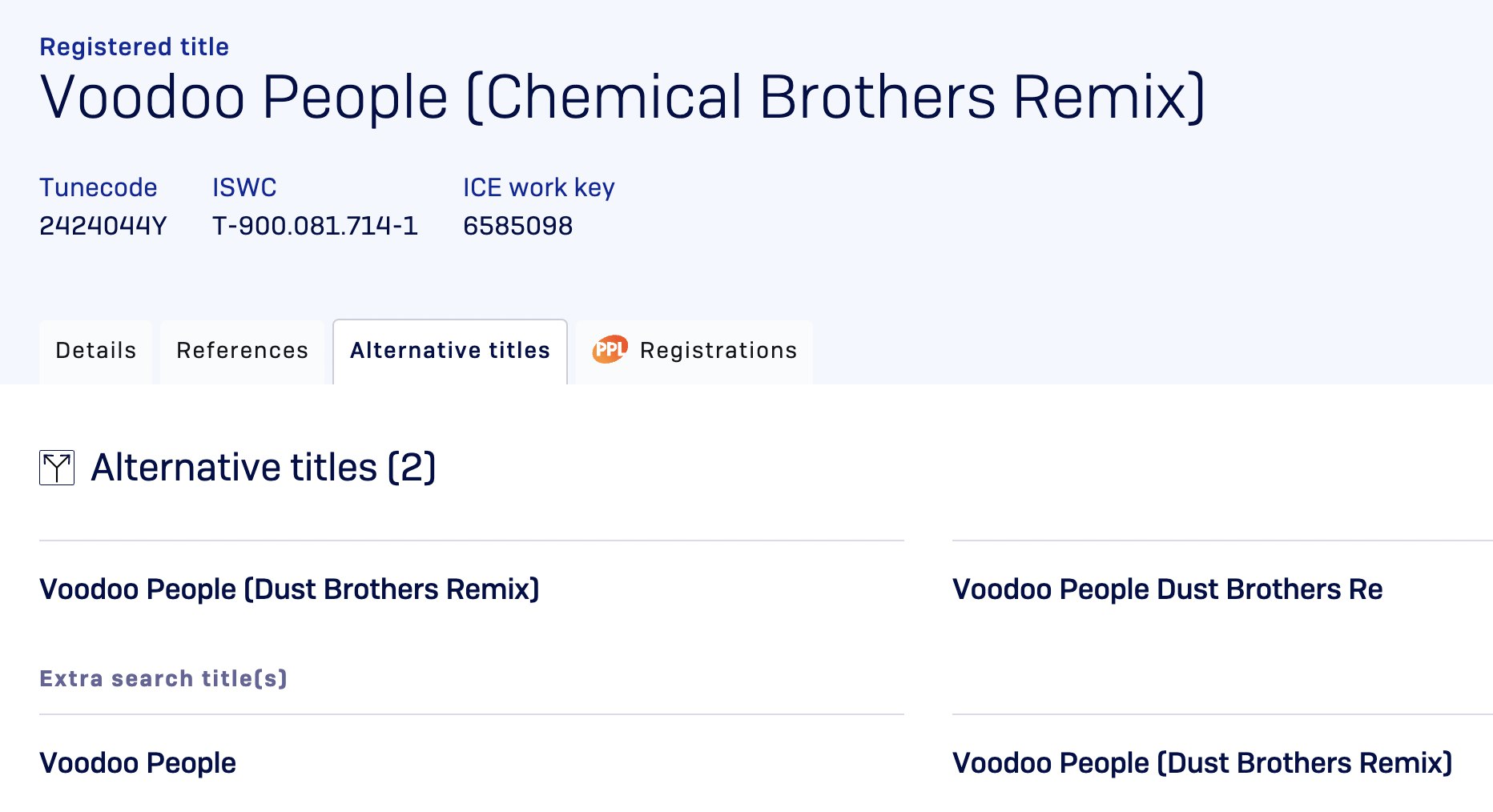

PRS & BMI Repertoire

However, at some point, XL Recordings seemingly resolved this issue, proving that the remix contained no direct sample from ‘For Pete’s Sake’, and that a single re-recorded line (not even a full verse!) could hardly be considered a proper cover requiring royalty payments. Nonetheless, the separate registration of the remix, created before this dispute was settled, remains in the databases as an independent entry to this day.

Six months before the release of the US maxi-single, an alternative version of the ‘Voodoo People’ video was created, set to The Chemical Brothers’ remix. This version differed significantly from the original and was broadcast on MTV and possibly other channels. Notably, no shortened version of the remix was made for this video — the full 5:56-minute version was used instead. However, a year later, in 1996, an official 4:59-minute edit of the remix was released on the compilation ‘Special Brew’.

The special video for The Chemical Brothers remix is not the only alternate version of the ‘Voodoo People’ video. Another edit exists, set to the original track. This version also features numerous unique scenes and shots that do not appear in other edits. There is a chance that this was the very first rough cut, produced as a promo for the upcoming single so that it could start gaining traction even before the final edit was completed.

In a conversation with All Souvenirs, Mark Reynolds, the original video editor, revealed that neither he nor director Walter Stern were involved in the alternative versions of the video — they worked exclusively on the final cut, which appears at the beginning of the ‘Electronic Punks’ VHS and on the ‘Their Law’ DVD. At some point, XL Recordings obtained the original footage and assembled their own edits. Producer Russell Curtis, who was involved in the shoot from the very beginning and was the one who organised everything, also confirmed that all of these alternative versions were created by the label, without any input from the director or the editor.

Russell Curtis for All Souvenirs: ‘All the unedited footage would have been returned to XL Recordings, and they can do whatever they want with that, so presumably they had someone else re-edit it. They didn’t seek or need approval from many of us, only the band I guess.’

Walter Stern for All Souvenirs: ‘An additional point is that MTV demanded a different version for daytime TV (pre-9 PM), so there was a version made with a lot of blurring out of the offensive bits (which was a lot of the video). They were on their last warning from the regulatory body.’

One way or another, the filming process and the editing of the ‘Voodoo People’ music video is a fascinating story in itself, deserving a closer look.

Music Video

Overall, ‘Voodoo People’ perfectly combined elements that had previously seemed unthinkable in The Prodigy’s music. The track opened with a powerful guitar riff, directly sampled from Nirvana!

Liam Howlett for Martin James’ ‘We Eat Rhythm’: ‘I’d always ignored anything that was in any way rock because it just meant leather jackets and greasy hair to me. Then I heard ‘Nevermind’ by Nirvana and it just blew me away.’

The track itself was already a surprise for electronic music fans, and in the first part of our article about it, we explored the details of its music production in depth. However, the ‘Voodoo People’ video further cemented The Prodigy’s status as innovators — not just in sound but in visual style as well. The former ravers in bright outfits now appeared in a completely different light: more mature, fierce, and uncompromising. With the release of ‘No Good (Start the Dance)’, the band first introduced a new, more refined image. That video marked their first collaboration with British director Walter Stern, and his second video for ‘Voodoo People’ took this transformation even further. By mid-1994, The Prodigy looked far more like dark, stylish grunge icons than the carefree clubbers in fluorescent outfits they had once been.

Select Magazine: ‘Liam Howlett sags in the heat and his battered suitcase tumbles down a small gully. He is standing in the middle of your actual steaming hot fruit-fly packed mosquito-convention tropical palm tree grove. His suitcase is supposed to contain The Prodigy dancer Keith (patience, we’ll explain later), but it’s actually full of coconuts and he’s just had to drag it half-way across this idyllic-looking but frankly treacherous trench-maze of a plantation. It weighs a ton. There are coconuts to the left of him, coconuts to the right of him. He’s going to break his ankle on one at this rate. And it’s blistering out here.’

Saint Lucia, the third southernmost island in the Windward Islands chain, is a true Caribbean paradise. This was the location The Prodigy chose for their fresh video. In mid-1994, this decision seemed unexpected for a band that, just a year earlier, had been filming low-budget videos between tour dates. Russell Curtis recalled that the team had considered other locations before settling on this one.

Right: One of the beaches in Gros Islet (St. Lucia), where the shoot was done. (Source)

Russell Curtis for All Souvenirs: ‘Yes it was an unusual choice! Walter knew it had to look like somewhere that voodoo was practised. We thought about Haiti, but it was too dangerous. Then we thought about New Orleans, but that was too dangerous and too expensive. I think Walter’s parents had been to St Lucia so we went there. It was still a small budget, not as tiny as ‘Charly’, but actually not as big as ‘Fire’ from the first album.’

Walter Stern for All Souvenirs: ‘My parents visited Saint Lucia on a holiday. The location for the video was suggested by my Father who knew a lot about geography and also where was more likely to be okay to shoot in. Some places would be too tricky for filming.’

As Liam himself mentioned in Select Magazine back in 1994, the concept for the video was inspired by voodoo scenes from ‘Live and Let Die’ — the eighth installment in the James Bond series. However, the team aimed for a grittier and more intense visual style, reminiscent of ‘Apocalypse Now’.

The crew was kept small, just because this was the only way to bring the project to life within the available budget. Package tours were booked for all participants, including the band, director Walter Stern, producer Russell Curtis, DP Joachim Bergamin, assistant director and camera assistant Rick Woollard, as well as Emma Davis, who covered the art department and make up/wardrobe. Some band members brought their girlfriends along, but Russell recalled that this created a certain level of tension: ‘Not sure if the girls knew who they were supposed to be there with!’

The filming equipment was brought in illegally, as the budget didn’t allow for the standard customs clearance process and deposit payment (a common practice to prevent unauthorized resale of imported gear). Since the video was shot on 16mm film, there was a substantial amount of equipment. All the props, voodoo cards, skulls, paint, and other items used by Leeroy in the video were also transported in an innocent-looking suitcase. Getting everything through customs was a nerve-wracking experience, but fortunately for the team, it all went smoothly without any incidents.

Upon arrival, the crew stayed at a hotel in the capital, Castries, heading out early each morning to film deeper in the woods. During pre-production, the team found a local fixer who helped with casting, locations, and everything else needed for the video. Seems like he worked in forestry but apparently did side jobs like this as well.

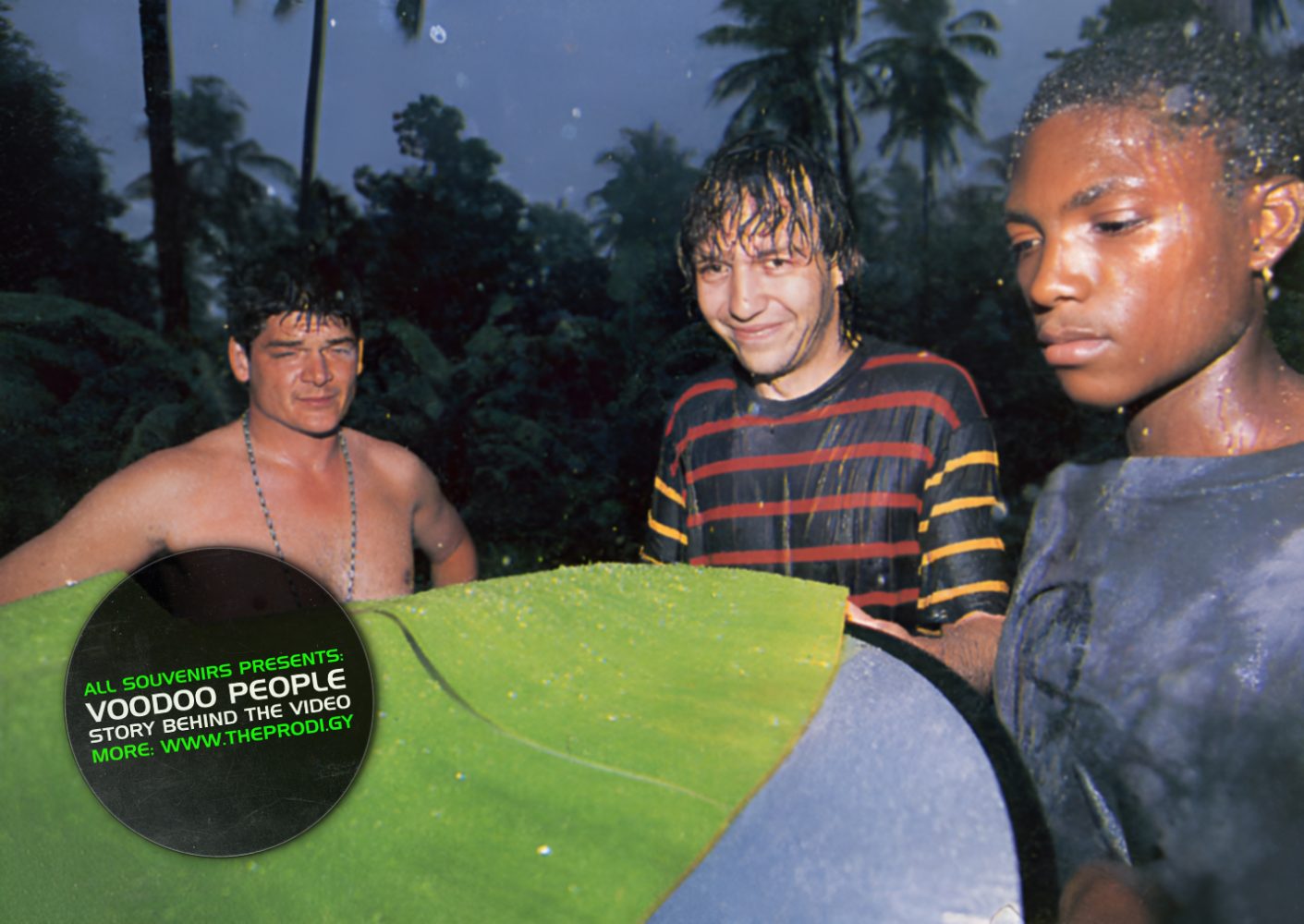

Walter Stern (centre), camera assistant Rick Woolard and passing helper protect the delicate camera with a pocket tarpaulin.

Captured by Mick Hutson

The original plan was to buy a cheap car and cut a hole in the roof for Leeroy to stick his arm through, but they couldn’t find a suitable vehicle. Instead, the team rented a couple of jeeps, one of which was modified for hours — its roof was covered with bamboo, cut on-site, and the body was heavily coated in dirt for a rougher look. With the small crew, even Russell had to take part in these modifications.

Leeroy Thornhill recalls another amusing incident with this jeep in his book ‘Wildfire’. While driving through the mountains, the crew unexpectedly got stuck in a traffic jam — locals had set up a car wash right in the river. When, after half an hour, it was finally the crew’s turn, the washers enthusiastically jumped on their carefully dirtied vehicle. Attempts to stop them were met with nothing but a shrug from the head washer, who refused to let the jeep go without payment. Explaining that the dirt was intentional didn’t work, so in the end, the team had to pay just to keep the car dirty. The washer never understood why they drove off so fucked up.

Select Magazine: ‘The following morning, rainy season deluges have soaked the shoot down to a dripping rabble. They’ve already completed one shot, of the jeep crashing headlong into a skull on a pole, known as an obeah stick and used in the rituals. As far as local blasphemy goes this is probably up there with blowing your nose on the Turin Shroud.’

The shoot was a real challenge. The crew was small, the heat was unbearable, and the work was physically exhausting. For the band members, especially Keith, it wasn’t easy either — particularly the scene where he was locked inside a suitcase and had to cut his way out with a knife. Iconic photographer Mick Hutson also flew to the island with the team, capturing not only this moment but many other striking images from the shoot.

It’s also worth noting that the Nirvana connection in ‘Voodoo People’ extended beyond the track itself. In Mick’s photos from the shoot, Keith Flint can be seen wearing the same style of sunglasses as Kurt Cobain.

Select Magazine: ‘After days of watching himself get thrown off cliffs, bounced down gorges and generally buggered about, it is Keith’s Big Moment. He will be zipped up inside the suitcase and must cut himself out with a Stanley knife before the oncoming jeep — driven with Ayrton Senna-like abandon by Maxim — flattens it. One take. No reshoot. And, ladies and gentlemen, Keith is doing his own stunts. ‘What’s my motivation?’ — ‘Your motivation is not to get run over by that fucking jeep. Now get in.’

Initially, the director planned for the formidable Baron Samedi to be played by Maxim throughout the video, but the charismatic Leeroy ended up fitting the role perfectly. Thornhill, who usually preferred to stay out of the spotlight, was surprised himself at how naturally he embodied the character during filming.

Leeroy Thornhill in his ‘Wildfire’ book: ‘Walter Stern and his team did another great job with the video and we were all happy with it. They hung Keith upside down by his feet from a tree and cut the rope before he was ready so he landed on his face; they had us running through plantations with snakes and spiders in; I was hanging on to the roof of a moving car – health and safety in full effect.’

After the main part of the shoot was completed and most of the crew had left the island, Walter and Russell decided to stay a little longer — to take a breather and film some POV driving shots, as well as capture the wild dance scene with colorful paint, where the dancing children appear to fall into a trance. The video was shot over approximately four days in early July, almost simultaneously with the worldwide release of the album ‘Music for the Jilted Generation’ on July 4, 1994.

According to Russell, several knife-related shots had to be removed during editing due to MTV’s regulations. However, they managed to keep the footage featuring the children — Curtis was convinced those scenes would have to be cut as well. It’s possible that part of the ritual scene with Leeroy was also removed, but after so many years, Russell can no longer recall the exact details.

youtube.com/@maddogfilms | facebook.com/maddogfilms | instagram.com/maddogfilms85

The editing of the video was handled by two people: director Walter Stern and the previously mentioned Mark Reynolds (Mad Dog Films). They worked together, sharing the entire process — from selecting footage to the final assembly of the video. Just a couple of months later, Mark began working on the first official VHS release, ‘Electronic Punks’ (1995), followed by the legendary but still unreleased film ‘Mutant Dog’ and other projects related to The Prodigy.

Mark Reynolds via Vimeo: ‘I can’t remember if I was too busy or if I turned down ‘No Good (Start the Dance)’, whatever the reason I regret it. I do remember being at film school and seeing the video for ‘Everybody in the Place’ and hating it. Little did I realize this band would become one of my favorites to work with in the future.’

Reynolds and Stern locked themselves away in Mark’s editing studio, located in the basement of his home in Crouch End, London — a secluded spot far from the hustle of the music industry. They worked in near-total isolation, fending off unwanted visits from label representatives and marketing teams eager to interfere in the process. With over four hours of raw footage, Reynolds employed a unique method to structure the edit.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘Basically, when transferring the film, I would push a button on every angle/shot that was filmed, and this would generate a black-and-white image with a timecode. I’d end up with a roll or more sometimes. These would cover three walls, so while editing, we would be surrounded by every image of the video. If that makes sense.’

With this approach, Stern and Reynolds would go out in the evenings for food and drinks, discussing the edit before working nonstop until dawn. Stern would crash in the spare room, and this cycle repeated day after day, sometimes stretching for up to ten days straight. The combination of isolation, exhaustion, and hours spent working with intense visual imagery began to take its toll.

Mark Reynolds for All Souvenirs: ‘There was one night during the edit, around 3 AM, when I was lying on the floor taking a break. As I tried to get up, I felt a presence holding me down! This lasted for quite some time, to Walter’s great amusement.’

Whether it was the result of sleep deprivation or something else, the atmosphere in the editing studio remained tense and surreal. Without a doubt, it was exactly the kind of setting needed to create a video like ‘Voodoo People’.

Martin Roach in his ‘Electronic Punks’ book: ‘The video contained some genuine scenes of authentic voodoo which the band had to carefully research because of the nature of the occult, and there were scenes of human torture and rituals which eventually had to be cut from the MTV version to exclude the ‘scenes of distress’ once more’

Roach’s claim about the ‘genuine scenes’ always seemed somewhat dubious, though it certainly added a certain dark flavour the band was aiming for at the time. Considering that the team was genuinely wary of encountering actual voodoo rituals (which led them to reject several filming locations) this rumor appears to be little more than a marketing move. Russell Curtis agrees: ‘Yeah, not sure how genuine the voodoo scenes were to be honest!’. Mark also recalls that some of the footage was on the edge, but he personally doesn’t remember any ‘scenes of human torture’.

Incidentally, the aforementioned ‘Electronic Punks’ VHS features numerous amusing outtakes from the ‘Voodoo People’ video shoot, scattered throughout the film (you can also watch the same behind-the-scenes footage on ‘Their Law’ DVD). They serve as a reminder that behind their serious and dark personas were four fun-loving Essex dudes who enjoyed joking around with each other.

As for Mark, he owed his work with The Prodigy entirely to Walter. The two met at Bournemouth Film School, collaborated on several projects, and became good friends.

In upcoming articles, we will continue to explore the track-by-track history of ‘Jilted Generation’ and share even more rare details about the making of other The Prodigy videos.

Headmasters: SPLIT

Additional thanks to: Sixshot, Alison Fielding, Russell Curtis, Mark Reynolds, Walter Stern

Donate

- Tether (USDT)

Donate Tether(USDT) to this address

Great job